Editor’s note: This article is reprinted with permission from writer and urban planner Pete Saunders’ urbanist newsletter on Substack. “The Corner Side Yard” now offers paid subscriptions and will go behind a paywall as of April 1.

The first rule of real estate investing is “location, location, location.” But when it comes to our personal living decisions, other factors that figure prominently seem to receive little mention.

Those include:

- An unspoken dimension to the “where” factor gets overlooked.

- The “what” side has a mismatch, as little of what’s out there fits the profile of what many buyers and renters seek.

- Relatedly, the “when” factor receives too little attention as we discuss buyer and renter preferences.

There’s More to ‘Where’

At least two dimensions of “where” are at play when people are looking at neighborhoods to inhabit. The obvious is accessibility. People want to live in a place that has good access to the places they want to go — work, schools, shopping. People also want to move to places that have the amenities they seek: entertainment, parks and other open spaces, bike and pedestrian trails, and more.

Beyond access and amenities, however, lies another dimension that rarely is discussed publicly. That’s the metaphorical dimension — the narrative of a neighborhood that drives perceptions. People will often select a neighborhood purely using this dimension. If a place has a good reputation, it will attract people. If the reputation is negative, potential buyers will stay away. Real estate brokers understand this dimension.

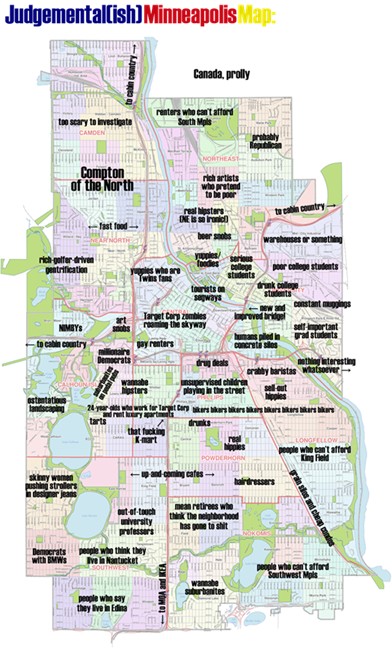

Have you ever heard of Judgmental Maps? I first encountered these maybe a decade ago, and their time probably has come and gone. However, these maps crudely get to the metaphorical dimension I’m talking about.

Consider this judgmental map of Minneapolis, with its references to neighborhoods labeled “people who can’t afford southwest Minneapolis,” “beer snobs,” “out-of-touch university professors” and “people who say they live in Edina”:

At one time, virtually every major city in the country had a judgmental map. I see now that the number of judgmental maps has declined. But this recently posted map of Minneapolis tells one person’s image of the city. This can be read as humorous, but it speaks volumes about how people outside of a neighborhood perceive life within it, true or not.

Ultimately, the perception has economic consequences:

- It determines who investigates neighborhoods for housing.

- It determines commercial development activity.

- It factors into public infrastructure investment decisions, like schools, parks and roadway improvements.

The longer that such a perception persists for a community, the longer it suffers economically and socially.

Monoculture vs. Adaptive Communities

Next up is the “what” of what’s built. I’ve argued for some time that most large American cities have an advantage over suburban areas because they’ve been built to adapt to changing conditions, and many suburbs are examples of what would be called monoculture in an agricultural sense.

Suburban communities increasingly seem to have a shorter shelf-life than urban neighborhoods, because they haven’t been especially adaptive. It’s hard to attract buyers or renters to move to places that haven’t adjusted to contemporary conditions.

A three-bedroom, one-bath home with 1,200 square feet of space may have once suited a two-parent, four-children household, but no more. The same house might be too big and cost too much for a single buyer or renter, or be located too far from the amenities they desire.

The Importance of ‘When’

This leads directly to the “when” of what’s built. Real estate brokers can tell you all about the preferences that buyers and renters bring to the table, and I think time plays a big part. In fact, I believe there’s a spectrum.

In large cities, I see a distinct preference for pre-World War II structures that have been updated to contemporary standards. After that, pre-WWII structures that haven’t been updated.

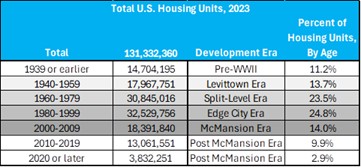

After World War II, we entered into the early development of modern suburbia, and we saw two suburban development eras — the Levittown era (1940-1959) and the split-level era (1960-1979) — that aren’t especially popular now but make up quite a bit of the housing market today. They’re followed by suburban development patterns, the Edge City and McMansion era patterns, that are losing much of their luster as well.

Buyers and renters express a clear preference for new development, as long as it fits their needs. I contend that our nation’s housing crisis is less about the pure number of housing units compared to the number of people seeking housing. Instead, a clear demographic case can be made that simply not enough housing meets the preferences of today’s buyers and renters. More broadly, there’s not enough of the kinds of neighborhoods that people are looking for, thanks to the suburban-style development of the past 75 years.

The following table illustrates the age of housing structures in the U.S., with nearly half having been built between 1960 and 1999. This data is from the 2023 American Community Survey’s one-year estimate of housing unit age:

Nationally, more than 37 percent of homes were built between 1940 and 1979, which I categorize in the Levittown and split-level eras of post-WWII suburban housing construction. Homes during these eras have largely lost their charm because they don’t support the demographic and lifestyle changes we’ve made over the last 75 years: more single-person households and fewer children. That is rapidly becoming true for Edge City (1980-1999) and McMansion era (2000-2009) development patterns, which make up nearly 39 percent of the nation’s housing stock.

In other words, some 75 percent of the nation’s housing stock is rapidly losing favor among today’s buyers and renters. There’s not enough new housing, and the more flexible development from earlier eras is disappearing. When one considers each of these factors, it’s clear that a housing mismatch is at the heart of the nation’s housing crisis.

Another factor influences housing decisions: the “who” factor. The answer to the question of “who was this community built for?” can shape the perception of a neighborhood for generations. So much so that I see it as worthy of its own post.

Photo at top by Michael Tuszynski on Unsplash.