Summit Hill, Frogtown, North End, Summit-University

August 7, 2024 – 21.6 Miles

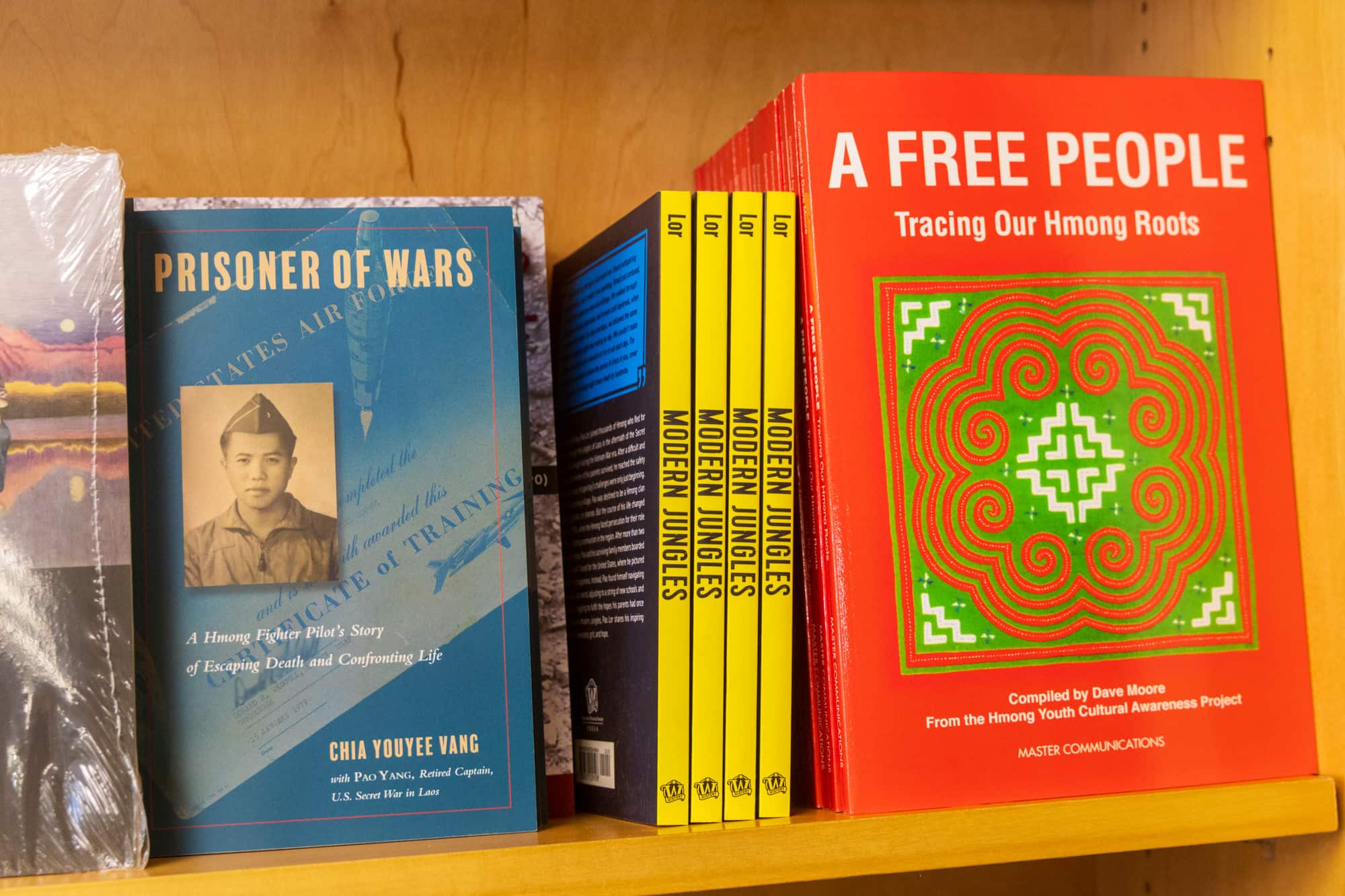

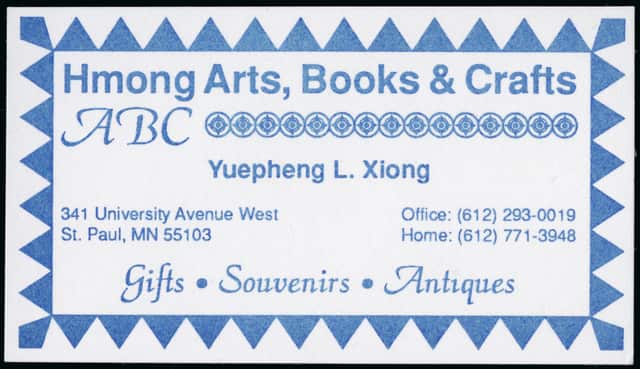

St. Paul is home to about a dozen independent bookstores. One of them has the distinction of being the world’s first Hmong bookstore, established on University Avenue in 1995. The Hmong ABC Store, now in Hmongtown Marketplace in Frogtown, remains the only Hmong bookstore, not just in St. Paul, but anywhere in the world.

Husband and wife Shoua V. and Yuepheng (pronounced “yoo peng”) Xiong own the Hmong ABC Store. Natural light from two windows, along with carefully placed books and colorful Hmong fabrics, dresses and embroidery, make the store warm and inviting. On a couple of my visits, hints of the sweet smell of freshly brewed Hmong tea wafted through the store.

Both are proud of the important role their store has played within Hmong society and among those interested in Hmong culture for more than 30 years.

Yuepheng hatched the idea of opening the store when he was a student at the University of Minnesota. “ The more I studied, the more research I know that we don’t have books to help the community with Hmong resources. And I believe at the time that eventually there’ll be more Hmong readers and there’ll be more Hmong writers in the future.”

So Yuepheng took a break from school to pursue his dream. “ I have to a postpone school for two quarters to do research and to find out what the publishers are and how to get books to sell. And at the time, we don’t have this many books on the shelves.”

“ I decide to create my own history for being the first Hmong bookstore.”

Yuepheng Xiong

In 1995 he opened the Hmong ABC store in a small space on University Avenue in St. Paul. “We rent there for several years and [then] we purchased a building: 298 University Ave.” The next, and current, stop for Hmong ABC was Hmongtown Marketplace at 217 Como Ave.

“Two thousand ten we moved here. The recession, the light rail. We know we couldn’t make it, so that’s why we decide to move here.”

The name Hmong ABC stands for Hmong Arts, Books & Crafts. It came about, according to Yuepheng, because when he opened in 1995, published works by and about the Hmong were scarce. “We couldn’t fill the whole store. So that’s why we carry many other gift items and clothing. And eventually, within the last several years, my wife began to carry Hmong embroider clothing, Hmong fabric, clothing like this dress and clothing, which is popular in the community now.”

Hmong ABC today carries a significantly larger variety of books than when Yuepheng started the business. “At the time, most of the books are by non-Hmong. Very few Hmong authors, but now you can see most of the books are by Hmong authors.”

The biggest reason for the rarity of Hmong authors decades ago is that the Hmong language lacked a written component until the middle of the 20th century, and even then, it remained oral. “Legends say that we have our own written language, but it was lost, maybe hundred or a thousand years ago. We don’t know when. That’s only myth and legend. What we have right now was created for us by missionary in 1953, so we don’t have a written language until 1953 for the Hmong people in Laos and for those in China, not until 1955, ’56.”

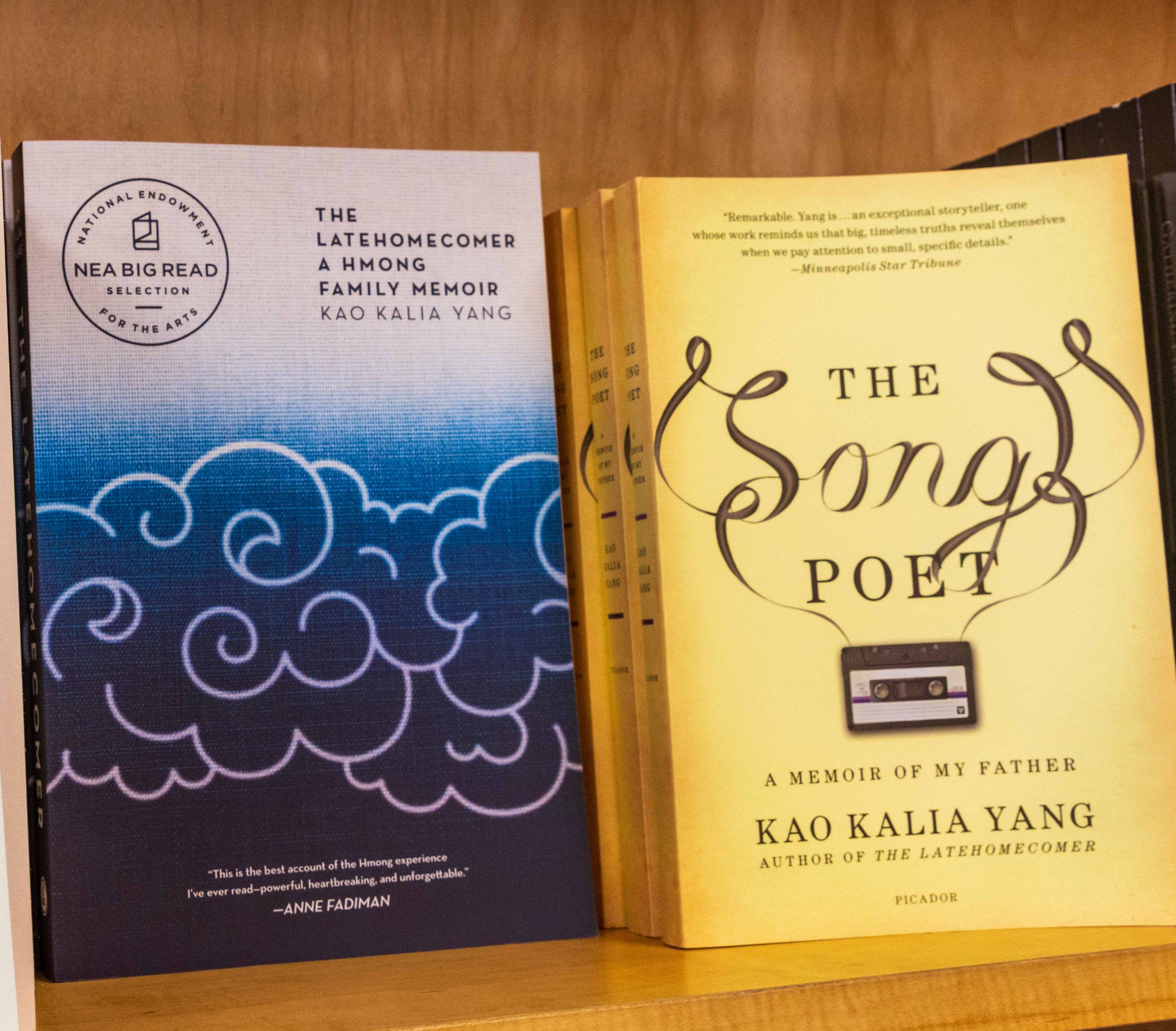

Today, said Yuepheng, Hmong-centric books are much more available. “We carry a lot of books both by Hmong and non-Hmong. History, culture, immigration, romance, children’s books, Hmong culture, ritual books, language, dictionary.” A few of those Hmong writers have made the big time. “We have some mainstream Hmong authors so we’re very proud of them and mostly our woman. So very proud of Hmong girls and woman in this country who accomplished a lot.“ Among those are Kao Kalia Yang, an award-winning author of memoirs and children’s books who happens to live in St. Paul.

While a majority of the store’s sales come from walk-in customers, it receives substantial bulk book orders from schools and libraries.

Shoua Xiong and Yuepheng Xiong are the only employees of Hmong ABC so they work every day of the week. “Our children now encourage us to get a day or two off, but we say, ‘Well, we have nothing to do. We just come here every day. We enjoy being here.'” Their six children helped out in the store when they were younger but no longer do now that they’re adults.

Beyond the Hmong ABC store

Working at a small business seven days a week would have most people longing for time off, but not Yuepheng. On top of his role at Hmong ABC, he’s produced a series of video documentaries about Hmong history, Hmong history in China, the Secret War in Laos, and the refugee experience in Thailand.

Another venture in which he immersed himself was establishing the Hmong Archives in 1999. “I co-found the Hmong archives, which we have more collections than any other places in the U.S. We have over a thousand donors, and we have over 200,000 items on Hmong.” (The Hmong Archives, housed within the East Side Freedom Library, will be the subject of a future ride and post.)

Yuepheng’s latest community effort is the co-founding of the Temple of Hmongism. Hmongism, according to the organization’s website, is a simplification of traditional religious practices to make them more affordable, less arduous and easier for all to participate. “When we talk about Hmongism, the main issue that pull us together is the funeral. But not limited to funeral. We do wedding, we do shaman rituals to help with illness, etcetera, and other rituals, too.”

And, he added, “[In] 2008, as you know, we have the recession. We all struggle financially, but especially our funeral expense are very costly.” Exactly how costly shocked me. “ If I were to pass away doing the traditional way before we simplify, it would be 75,000 [dollars] up per funeral. Some people would do up over 100,000 [dollars] per funeral.”

Traditional funerals, Yuepheng pointed out, are very complicated, long and usually well-attended events. “ Food are elaborate, decoration and all the rituals are several days long. And a lot of people. So you have to feed all these people, so many people struggle financially to have the funeral and to bury their loved one. Before we have Hmongism, some [funerals] started on Friday and burial on Monday,”

Funerals are significantly less stressful for the grieving under Hmongism. “ Not much to do because we have our own priest who will perform the ritual so the family doesn’t have to know too much, [or] to do a lot of thing compared to the traditional. So it’s not difficult for the young generation and not difficult for non-Hmong because in the community we have a lot of intermarriage. So we have both non-Hmong and Hmong to come to a funeral.”

The Temple of Hmongism, said Yuepheng, is likely the first to declare that Hmong people have a religion. “In the past, many people, community people, some scholars, argue that we don’t have religion, we only have culture. So through our research, we conclude that yes, we have a religion because we believe in the soul after we pass away, where do the soul go? And we also have original sin.”

Hmongism continues to gain acceptance and not just among the more Americanized. ”It’s a mixture of people. Some rich people, some poor people, some have extended family, some no, some old, some young. It’s not unique to any particular group,” Yuepheng explained.

The Harrowing Escape from Laos

The Hmong are a Laotian ethnic minority, who lived and farmed in the highlands of Laos. In the early 1960s, the CIA began covertly recruiting Hmong men, and often boys, to fight for the United States against North Vietnamese and communist Pathet Lao (People’s Party of Laos) troops. This is known as the Secret War. Yuepheng’s father, Nhia Blia Xiong, was one of the tens of thousands of Hmong fighters mobilized by the CIA.

U.S. forces withdrew from South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia in 1973. Two years later South Vietnam fell to the North Vietnamese and the Pathet Lao, who took control of Laos. That left our Hmong allies and their families in mortal danger of being caught and tortured and/or killed. Many thousands fled Laos, while thousands more were captured or killed trying.

The exploits Yuepheng Xiong, his parents, siblings and extended family endured while fleeing their homeland, lifestyles, culture, possessions and some family, are similar to most Hmong. The obstacles they faced during the perilous trek—it took more than a month by Yuepheng’s estimation—are almost unimaginable, with unanticipated twists and turns and spontaneous decisions that had life or death implications.

Most left with little but the clothes they wore and perhaps a small personal item. People with young children carried them, while others lugged food, frequently rice. Once the rice was eaten, folks had no choice but to forage in the jungle for wild vegetables and bamboo shoots. Some resorted to theft in the face of starvation, according to Yuepheng. “Some uncles went back to steal enemy’s rice.”

Yuepheng and his family were part of an extremely large group that began the treacherous expedition through Laos together, hoping to cross the Mekong River to the relative safety of Thailand. “My father told me, ‘When you first gather do head counts, we have about 3,000 in the group.’ I forgot what my father told me. I forgot the number, but probably not more than two dozen that make it first trial.”

The many perils of crossing the Mekong River

Imagine the Mississippi River being three-quarters of a mile wide. Now imagine having to swim across the river—in the middle of the night, not knowing the strength of the current, and never before having seen the river. That is exactly what the Hmong had to do with the Mekong River to escape Laos after the end of the Secret War.

Yuepheng Xiong stated that most people attempted to cross the Mekong at night to have the best chance of avoiding capture. “ The section that we cross is very wide. We cross at midnight. Hmong people never see the Mekong River. So we cross at midnight. We only see the river right there, not too far. So we just keep swimming, crossing, paddling.”

Another danger, explained Yuepheng, was unfamiliarity with the river. “ There’s certain sections has some kind of island. Some people make it to the island. They thought it was the Thai side. They throw the floating bamboo or the floating tube away. And then they soon found out there’s that other channel on the other side. So those are likely being captured or killed.”

The river itself posed assorted hazards. “ Some people, the river spin them so they head back to Laos. So we have to look at a light, make sure we follow a light. Laos side was not very well developed, so it’s kind of dark. Thai side, it’s all light. So you have to look at those light.”

Drowning threatened all who attempted to cross. In fact, Yuepheng’s baby sister was lost to the Mekong, a tragedy that causes him to choke up with emotion more than 50 years later.

Most of Yuepheng’s family were not among the couple dozen who escaped Laos at that time. “When we were about a day’s walk from the jungle to the Mekong River, we were attacked. So people scattered, some people surrender, some people went back. Some people just sneak and hide in the jungle, which is our case.”

Of the family, only Yuepheng’s father, Nhia Blia Xiong, and one uncle managed to avoid capture. “ My father formed a team of five, so they left before we were attacked. But even though they heard we were attacked, they did not come back. They left to Thailand. So that’s why we didn’t surrender. We didn’t went back [sic] to where we come from. We just hid ourselves in the jungle waiting for my father and my uncle to return.”

As it turned out, Nhia Blia Xiong never did return from Thailand for the rest of the family. “…but my uncle come back and luckily he found us. So he bought medication. He bought those floating plastic tubes, which he used [to cross the Mekong.]

In another twist, Yuepheng’s uncle seriously injured his knee on the returning to the family from Thailand. As a result, he was unable to attempt the journey to Thailand again. He was forced to stay behind in the jungle with another uncle when the rest of the extended family were ready. That left Yuepheng—at 15 years of age—responsible for safely getting the group to and across the river. “ I was the oldest in the extended family of about 20 people. And people are so hungry, people don’t wanna stay anymore. So we left with the rest of the group.”

The next complication came after a different group of refugees just ahead of Yuepheng’s got close to the Mekong. “They capture a Lao farmer. And instead of having the Lao farmer go to the Mekong River, they were so hungry. So they want the farmer to find food for them to eat. So the Lao farmer came to his house, jumped the other side, ran.” Strongly suspecting the farmer would notify authorities who would return to capture the group, they scattered into the jungle to hide again.

The Xiong family managed to evade the Lao troops, regroup and continue warily moving toward the Mekong River.

After many days of sneaking through the jungle, up and down mountains and across valleys, the Xiongs arrived at the Laotian side of the Mekong River. “A distant nephew and I, we swim across, leaving behind my mother, aunts and cousins and siblings. So we swim across, we make it to Thailand, and then we were taken by the Thai authority.”

The family members who waited for help to cross weren’t as lucky. “Those we left behind were captured. So it’s only my father, my two uncles, and I will make it to Thailand without being captured.”

Yuepheng, his father, Nhia Blia Xiong, and the two uncles didn’t know the fate of the rest of the family who weren’t able to cross the Mekong. Nhia Blia Xiong paid people to discover their whereabouts. “ Probably several months, he learned that my mother and brothers, sister and aunts, they were captured and stationed in Pakxan, which is a city on the southern Mekong River.”

Once again, his dad had to pay people, this time to smuggle the family from Pakxan to Thailand. There they registered for asylum in the US and in less than a year, were approved and came to Chicago. From there, Yuepheng and his family lived in Wisconsin until the 1993 move to St. Paul-Minneapolis.

While Yuepheng has returned to Laos several times—to the Vientiane area and to Xiangkhouang Province, where he’s from—he didn’t feel comfortable visiting his hometown. Perhaps, he said, in the future. Meanwhile, he and his wife, Shoua, will continue serving the Hmong through the store and his work with the Temple of Hmongism.

The Frogtown Community Center

The gorgeous Frogtown Community Center inhabits the irregular spot of land where Como Avenue, Marion Street and Pennsylvania Avenue meet. It replaced the terribly outdated Scheffer Recreation Center in 2019.

The North End

Several blocks to the northwest on Como Avenue, a mostly topless bevy of bins or colony of containers perched in a lot.

The North End Neighborhood Organization, or NENO, occupies the interesting two story red brick building at 171 Front Ave. NENO, the District 6 Community Council, moved to the building about 2010, after it underwent a major renovation.

NENO Executive Director Kerry Antrim said in an email that 171 Front previously served as a grocery and a duplex. Remnants of its life as a grocery remain visible on the building’s west side. (click on a photo to enlarge it)

Despite it being early August with a temperature in the 80s, someone on the 100 block of Front Avenue was incredibly prepared for winter.

Wayzata Street West is but four blocks long, primarily fringed with single family homes. The 100 block, between Rice and Park Streets, offers a slightly different look from, not only the street’s other three blocks, but from many other of the city’s residential thoroughfares. Most conspicuously, it’s several feet narrower than “usual”, if there is such a thing in St. Paul. The one way aspect of the block is uncommon for a residential street.

As I revisited the conversation Yuepheng Xiong and I had, I am left with a lasting impression of the bravery, perseverance and resilience he and his family have shown. The traits that allowed them to escape the brutal regime in Laos also sparked their success in Minnesota. It also made me ponder how similar the experiences my own family members were when they immigrated to the U.S. more than a century ago.

Editor’s Note: A version of this story originally appeared in the author’s blog, “Saint Paul By Bike,” on March 7, 2025, and is reprinted with permission.