Minneapolis has several high-profile political races that could push the city in a more progressive and urbanist direction. Mayor Betsy Hodges, the incumbent, has drawn a wealth of challengers even though she has overseen some policy successes in her first term. Since all 13 councilmembers are up for reelection, many council seats could change hands. Since I grew up in Minnesota and lived in Minneapolis for three years and Saint Paul for a year and a half before moving to Seattle in 2014, I’ll be offering an outsider’s perspective, but comparisons to Seattle might have some insight for Minneapolis’ political and urbanism landscape.

Police Shootings And Racial Disparities

Minneapolis has been in the news for the wrong reasons lately. In July, an Australian woman was shot and killed by a Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) officer who was sitting inside a squad car at the time. Mayor Hodges fired Minneapolis Police Chief Janee Harteau shortly thereafter, leading some to ask why police chiefs are typically not fired when their officers kill a black man–for example when Jamar Clark was shot and killed by a MPD officer in 2015. Hodges appointed as acting police chief Medaria Arrandondo, a black police officer.

Last year another Twin Cities police shooting that went viral was when Philando Castile was shot and killed in 2016 by Officer Jeronimo Yanez with the Saint Anthony Police–a suburb just north of Minneapolis–during a routine traffic stop in Falcon Heights–another suburb just east. Castile’s girlfriend Diamond Reynolds watched in horror and filmed the aftermath with her phone to try to keep her four-year-old daughter calm and safe as Philando bled out and Yanez continued to point his gun at them.

Police shootings, racial violence, and criminal justice reform (or the lack thereof) are becoming a campaign issue, and so should they become a major issue for the urbanist movement. One place urbanist can help is increasing awareness of the role structural racism played in the history of American cities. White flight to government-subsidized suburban sprawl left cities to minority communities who overcame divestment to not only stabilize these abandoned neighborhoods, but also to create vibrant places. The success of minority-led urban communities ultimately drew suburban whites back into cities but the influx a wealthier group has displaced many of the people of color who made these places what they are. Along with displacement, gentrification means the flourishing of cultures incubated in cities is also imperiled as more homogenized white or globalized culture takes over, often bringing cookie cutter chain restaurants and franchise stores.

Minneapolis’s Stone Arch Bridge is a popular spot for tourists, wedding photos, selfies, joggers, cyclists, and pretty much all humans. (Photo by author)

Context: Needs Emerging During Growth Spurt

In some ways, Minneapolis is a good city for an urbanist. It boasts a robust park system built on an Olmsted plan. After long (and sometimes brutal) winters Minnesotans tend to flock to the streets, beaches, patios, playfields, farmers markets, and bike trails when spring finally arrives to make up for lost time. Minnesota’s urbanist community also an engaged community around urbanism and multimodal advocacy like this venue right here.

The off-street bike and pedestrian network is something to behold starting with Minneapolis’ crown jewel, the Midtown Greenway, a bike freeway through the heart of South Minneapolis. The on-street network still needs work but is probably more functional than Seattle’s–what momentum we had was stunted by the malaise of the Murray administration. One sign of progress on Minneapolis’ on-street network is a protected bike lane that will open as soon as the reconstruction of Washington Avenue downtown is completed. Third Avenue recently got a protected bike lane too, but the council flinched at a more ambitious plan to include a road diet and planters to better protect cyclists and green the street. Perhaps a new council would be more open to re-channelizing streets and more closely heed the precepts of the Complete Streets ordinance the council passed.

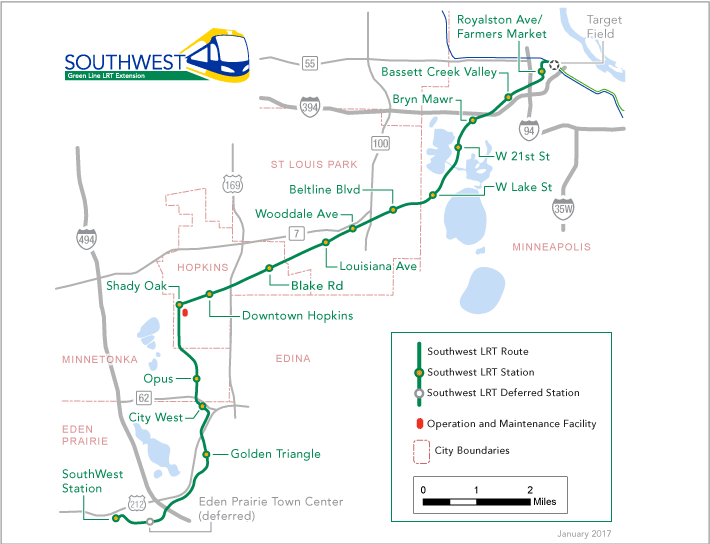

The alignment doesn’t hit many urban centers in Minneapolis, but does connect important job centers in the suburbs. (Met Council)

The addition of the Green Line, a center-running mostly at-grade light rail line which connects downtown Minneapolis to downtown Saint Paul, was a huge boost to transit. Minneapolis also got the jump on Seattle opening its first light rail line running to the airport and Mall of America in 2004 (now known as the Blue Line). Unfortunately further progress on the light rail network is in limbo following the Republican takeover of both the Whitehouse and Minnesota’s state legislature last year. Metro Transit is still hoping to open Southwest Light Rail (SWLRT) in 2021 despite delays and mounting uncertainty about funding.

Meanwhile, things appear to be moving more smoothly for Bottineau Light Rail, which would extend the Blue Line to the northwest suburbs and terminate in Brooklyn Park. The alignment leaves much to be desired–mostly avoiding population centers within Minneapolis to bee line for suburban park and rides. Northwest light rail could be turned into a much bigger asset by running it through North Minneapolis rather than through Theodore Wirth Regional Park for no apparent reason other than it’s easy and cheap–the 13-mile extension has an expected cost of $1.5 billion. With the project on track to open in 2022, it seems unlikely policymakers will change course.

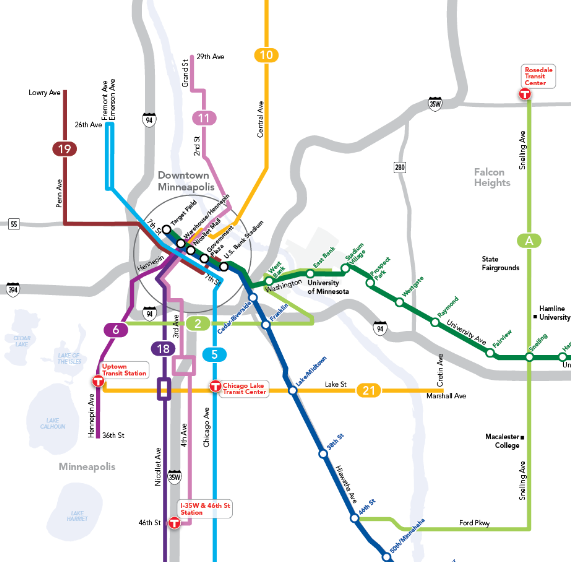

The High Frequency Network in Minneapolis. (Metro Transit)

Looking beyond light rail, bus service is spotty, which is reflected in ridership data. Metro Transit has implemented one bus rapid transit (BRT) line (the “A line” on Snelling Avenue in Saint Paul) and is planning more, although they’ve tilted toward suburban commuter service rather than a reliable urban grid. The flagship of the Twin Cities bus network is far and away the Route 5, which runs from Mall of America to Brooklyn Center–with average weekday ridership of 19,000. That beats Seattle’s highest ridership bus, the RapidRide E, which averaged 17,000 weekday rides at last count (the E is a 13-mile route while the 5 is about 20 miles.) Meanwhile, Minnesota’s new A line BRT clocked in just above 4,700 last year.

Minneapolis has welcomed new housing in some select areas, but has struggled to implement more permissive zoning more broadly. Big population gains may make that mission more urgent. After bottoming out around 368,000 in the 1990 census, Minneapolis has likely seen its population surpass 420,000 in 2017. On a pace of more than 6,000 new residents per year since 2010, Minneapolis is growing steadily. Much of that population growth had been concentrated in Downtown, Dinkytown, and Uptown, where many apartment buildings have sprouted near the Midtown Greenway. Development was relatively slow to take off along the Blue Line, but has recently picked up there and along the newer Green Line.

Forging Urban Solutions – transit

What should a candidate seek to make of these trends and the problems they present? The mayor and council cannot control the SWLRT funding, a big chunk of which is expected from the Feds through the New Starts program. However, the mayor and council will have a big say in optimizing the bus network. Metro Transit recently rolled out Transit Signal Priority (TSP) on the flagship Route 5 in hopes of keeping the busy bus on schedule. Lavishing attention on the city’s workhorse buses could help Metro Transit reverse its recent ridership losses, which have been blamed on cheap gas but certainly aren’t helped by slow routes stuck in traffic due to a lack of dedicated lanes.

Minneapolis established a value capture district in hopes of implementing the Nicollet streetcar. (City of Minneapolis)

Candidates could also have influence in guiding streetcar projects being kicked around now or in making the case for a bold new project. If SWLRT does keep moving ahead, the City of Minneapolis must come up with a plan to fund Midtown LRT which would provide a speedy alternative to the woefully slow Route 21. Civic leaders will need to follow a delicate path to sell the project of building light rail alongside the Midtown Greenway, which will temporarily interrupt the heavily used bike trail and inevitably draw out fears of decreasing quality on the trail. A good plan should be able to both ensure long-term viability of the greenway and provide excellent light rail service. The legacy rail trench made the Midtown Greenway possible, and it also what makes grade-separated light rail so reasonably priced in the corridor.

The bold idea I had in mind is a subway underneath Nicollet Avenue to relieve a transit bottleneck in Downtown Minneapolis. Unfortunately, the city is in the midst of a pricey Nicollet Mall beautification project that represents a squandered opportunity to do a cut-and-cover tunnel and a new excuse not to initiate one anytime soon. Instead the City has been exploring building a streetcar on Nicollet and Central Avenues, which would be much cheaper than a subway but not offer much in the way of time savings for transit users. When my new home passed a $54 billion transit package, I can’t help but dream bigger for my old home state. They identified a great corridor for improvement but selected the wrong technology; subway or a transit tunnel would attract many more new riders via its great speed and comfort and would scale up with demand much better.

Forging urban solutions – housing

As Minneapolis has grown, the need to reform zoning policy and increase support for affordable housing has grown too. Urbanists broadly agree about replacing single family zoning with more flexible zoning types that would permit missing middle housing like duplexes, fourplexes, rowhouses, and courtyard apartments and, in some places, dense multifamily zoning. Practical strategies to actually achieve broad zoning changes may need to apply to a wider audience, though. One way to reframe upzones is to pair them with inclusionary zoning, and that strategy seems to working in Seattle as the council successfully passed another neighborhood upzone on October 2nd. Councilmember (and zoning committee chair) Lisa Bender led the effort to study inclusionary zoning and craft a proposal, which seems likely to be brought forward soon. Inclusionary zoning can help build coalitions around upzones, and candidates who’ve run from the issue maybe shouldn’t.

Beyond inclusionary zoning, strong candidates should be presenting a vision for how they will increase funding for affordable housing or otherwise produce more low income housing. Minneapolis’ housing market hasn’t seen the crazy rent jumps some coastal cities like Seattle have seen, but that’s no reason to get complacent either. It’s best to be proactive. Something crazy could happen like Minneapolis securing Amazon’s second headquarters, as local leaders are falling over themselves to do. If something like that happened, Minneapolis might find itself in an affordability crisis very similar to Seattle’s.

This post was adapted from a post that first appeared in The Urbanist.