Macalester-Groveland, Lexington-Hamline, Frogtown, North End, Downtown, Irvine Park, West 7th

23 Miles

Lexington-Hamline

Though my travels around the city concentrate on streets, now and then I find my way onto an alley. There are about 330 miles of alleys in St. Paul made of several different surfaces. Most are blacktop, though some are gravel, and a few are dirt. Until my friend Rucksie clued me in, I hadn’t the faintest idea that at least one alley retains a long-antiquated surface – wooden block pavement.

Just one block of the Summit Avenue-Portland Avenue alley — between Lexington Parkway and Dunlap Street — features the wood block pavement. Wooden pavement was used in St. Paul and other U.S. cities between the mid-1850s and 1870s before brick and cobblestone pavement replaced it.

Summit-University

North End

After moving into the North End, I chanced upon a park at Mackubin and Stinson streets. Front Park has three ballfields, an appealing skate park (to this non-skater) and a pleasant bathroom building.

A pre-teen boy had the Front Skate Park course all to himself. He hardly noticed me and my camera because he was concentrating on the quarter pipes, banked ramps and stairs. I struck up a conversation with one of two other guys, the boarder’s brothers, who were there watching.

Mark, the oldest of the three brothers, said he works across the street from Front Skate Park. Mark went on to say that Max, the young boarder, got into the sport about a year ago. “He’s 11. He’s still new to it, but he’s super ambitious, so while I’m at work, he can come over here and skate.”

Mark told me this was only the second time Max was working out at Front Skate Park. “Now that he’s out of school, I think he’s going to be here all the time. It looks like he’s really enjoying himself. Even though he’s by himself, he definitely takes that opportunity to try to hit every single trick at this park.”

According to Mark, Front Skate Park starts filling with boarders about 2 every afternoon. “They know there’s going to be little kids here, but they keep them over to the side. It’s a smaller ramps over there. The kids stay over there. So the skateboarders run these [bigger] lines. They have that unwritten rule.

“I think the skate park has its own environment,” Mark continued, “where there’s kind of this respect with the kids.”

Max was too busy skating to talk to me, and true to Mark’s words, he was still skating as I biked northward from Front Park to my next North End stop.

The St. Paul Karen Seventh-Day Adventist Church, in the heart of the North End, opened in about 2018. Previously the North Emanuel Lutheran Church congregation occupied the building from its 1961 construction until September 2017. The original Emanuel congregation was organized by Swedish immigrants at Mathilda and Hatch in 1891, according to the website Who Built Our Capitol. Decades later Emanuel was renamed North Emanuel Church.

With more than 10,000 refugees, Saint Paul is home to one of the largest Karen (pronounced ka’REN) populations in the United States. Like many refugees, the Karen are an ethnic minority that fled persecution, in their case, from Burma (Myanmar).

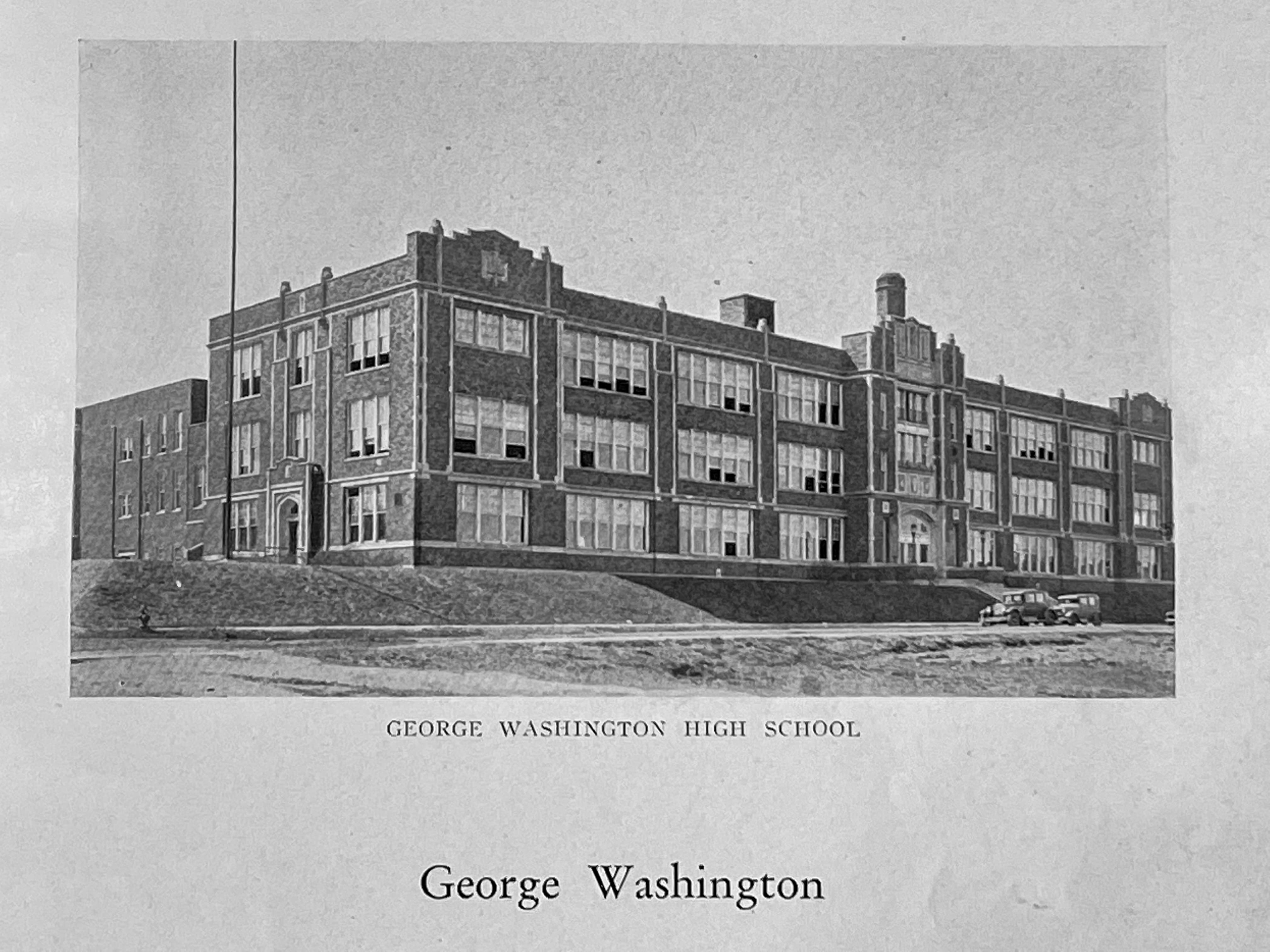

This beautiful building is Paul & Sheila Wellstone Elementary School. Conceived and built as George Washington High School in 1926, the building plan included lots of space for athletic fields — three blocks’ worth to be precise. Washington drew public school students from the North End for more than 50 years.

Clarence “Cap” Wigington, the first African American municipal architect in the United States, was the lead architect of Washington High and many other buildings in St. Paul.

Washington’s last high school class graduated in 1979, 50 years after its first. The building became a junior high and then middle school before being converted to an elementary. The Washington name disappeared from Saint Paul Public Schools (SPPS) buildings for several years in the early 2010s but reappeared as Washington Technology Magnet School at the former Arlington High School on Rice Street.

The City of Saint Paul has asked the state legislature to help fund a new community and recreation center at 1025 Rice Street (at Lawson Avenue), just north of the Rice Street Library. The design for the 25,000-square-foot North End Community Center features multi-purpose community rooms, a teaching kitchen, youth and teen rooms, a gymnasium, and dance, fitness and study rooms.

A short distance from Wellstone Elementary is the Church of St. Bernard, a spiritual, visual and auditory icon on the North End. This building, at 187 Geranium Avenue West, opened in 1906 after the Catholic parish outgrew its original building — and several additions — nearby.

St. Bernard’s two bell towers are visible from around the North End, and its bells, refurbished in 2019, resonate throughout the neighborhood. The three bells, according to The Catholic Spirit website, have names. The Virgin Mary, Help of Christians is the bell in the north tower, and St. Bernard and St. Joseph are the two in the south tower.

Jenaro is the maintenance man for St. Bernard’s. He and I met and talked as I took pictures. Born in Texas, Jenaro came to St. Paul 39 years ago, when he was 21. One of Jenaro’s brothers lived here and every time he visited Texas he would prod Jenaro to come check out Minnesota. “I said, no, it’s too cold,” he told me with a laugh.

Jenaro’s brother replied that it was summertime, and warm. “‘So I said, ‘OK, I’ll try it.’ And here I am, after 40 years.”

Some years later his brother left town — without Jenaro. “He never came back for me and then he moved to Milwaukee and then he went back to Texas.”

Jenaro landed a job with the City of Saint Paul in 1981. “I worked at the city Parks and Recreation for two years. And then I worked at Regions Hospital for two years and then they laid me off,” he said.

Jenaro’s next stop — the Church of St. Bernard and its affiliated elementary and high schools — turned out to be his last. He was hired for the school’s cleaning crew but quickly realized that cleaning wasn’t for him. So he went to his boss. “I said, ‘I’m gonna quit.’ And then he asked me, ‘Well, what are you wanting to do?’ I told him that I like to use my mind and my hands. ‘I want to do what you’re doing. You know, like fixing things.’”

Unexpectedly, his boss agreed. “I said, ‘How can I do it if I’m working?’ He says, ‘Go to night school.’ It scared me a little bit. I went and got my boilers license and whatever else he asked me for.” Upon completing his certifications, Jenaro got “a bunch of work orders” and was on his way. From that day forward, he has been fixing sinks and faucets, cutting the grass, shoveling snow, cleaning and preparing the boilers for the long, frigid winters and maintaining other mechanical equipment around the church and school.

Jenaro added that his boss did not abandon him, encouraging him instead to ask questions and teasing that he “may or may not” answer. “I learned a lot, and otherwise I wouldn’t be here.”

One of Jenaro’s duties was related only peripherally to building maintenance. “The [school] principal used to give me the bad kids that did bad things and he told me, ‘Jenero, they’re going to work with you, and find something they don’t like.’” He laughed, recounting how he would tell the kids: “Hey, you know, I want you to do this, and if you do, we won’t have a problem. If not, you know how John [the principal] is; he’ll get you back in there.”

Jenaro’s time at St. Bernard’s comes to a close in October, when he will retire, so he’s training his replacement. “I’m just showing the other guy how to do it. He’s been here two years. He’s pretty good, a real intelligent guy.”

Jenaro’s retirement plan is focused around his family — especially his 11 grandchildren and two great grandchildren, most of whom live in the area.

“Where did the time go? Who knows? Yeah, but thank the Lord. We’re still here and healthy, and no problems. I can’t ask for more, you know. Now all I ask him is to give me a little time so I can enjoy myself.”

Seems like a modest request, with all that Jenaro has done to serve St. Bernard’s Church and School, and the Lord.

I began an indirect trip home, but I wasn’t quite done with the North End. I inadvertently bumped into Lewis Park as I rolled south on Albermarle and came to Wayzata Street. I’d never heard of the one-block square city park dedicated in the 1880s by and named for land developer John P. Lewis.

I learned through a bit of research that Lewis Park is no more, despite the sign. The City Council voted in March 2021 to rename it after civil rights figure Roy Wilkins, who spent much of his youth living with his aunt and uncle in the neighborhood. New signage and better lighting will be installed when more money is available.

West 7th

From the North End I journeyed to West 7th, where I checked out a most unconventional construction site. What makes the $40 million, 192-unit apartment complex being built at 337 W. 7th St. unique is its modular construction. The seven-story Alvera is the largest prefabricated modular building ever built in Minnesota. The lifting, stacking and securing of dozens of precisely built individual modules had been completed before this ride.

I was fortunate, however, to bike by with my camera on June 4th as module installation was going full tilt. Imagine putting together a life-sized three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle, and you have an idea of the complexity.

at the factory.

Rise Modular of Minneapolis fabricated the modules for the Alvera in its Owatonna plant. Rise claims its modular process is quicker and less expensive than traditional construction. It will be interesting to see whether modular construction of apartment buildings becomes commonplace.

Below is the map of this ride. As always, the map is Zoomable. (All photos are by the author unless otherwise noted.)