July 6, 2022

Highland Park, West End/West 7th, Downtown, Lowertown, Battle Creek

24.3 miles

Below, the map of the July 6, 2022 ride.

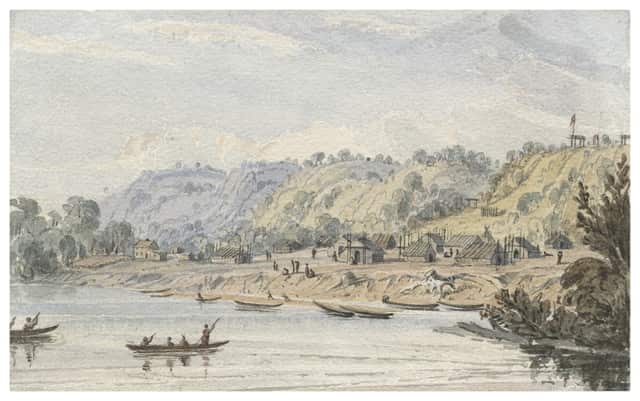

St. Paul is a river town. No surprise there. What may be is that our city has more shoreline and publicly owned land along the Mississippi than any other city along the 2,300-mile run of the river. Native peoples, and later, Europeans used the Mississippi in many ways — for exploration, as a path to move people, crops and later, commodities, and even as a sewer and industrial waste dump. Industrialization, however, strangled the ability to use (and the interest in using) the river as a recreational resource.

Access to the Mississippi in St. Paul, especially since the 1990s, has gradually improved with the relocation of industry and roads. Still, much of the river remains frustratingly difficult, even impossible, to get to, so advocates keep pushing for significantly more and better connections. Three extensive and intriguing projects that would do just that are in various stages of planning right now.

One of them is why my ultimate destination this overcast day was Pig’s Eye Regional Park, the city’s largest and, paradoxically, least known and most difficult to get to park. Mary deLaittre, executive director of the Great River Passage Conservancy agreed to meet there to talk about plans for this unique, beautiful, muddled place.

Lower Landing Park

On the way to Pig’s Eye Park, I rode east on the Samuel Morgan Trail, which follows Shepard and then Warner Roads. I paused to investigate some recent improvements at Lower Landing Park, east of Downtown, on Warner Road. The enhancements were completed in advance of the Viking River Cruise visit to St. Paul.

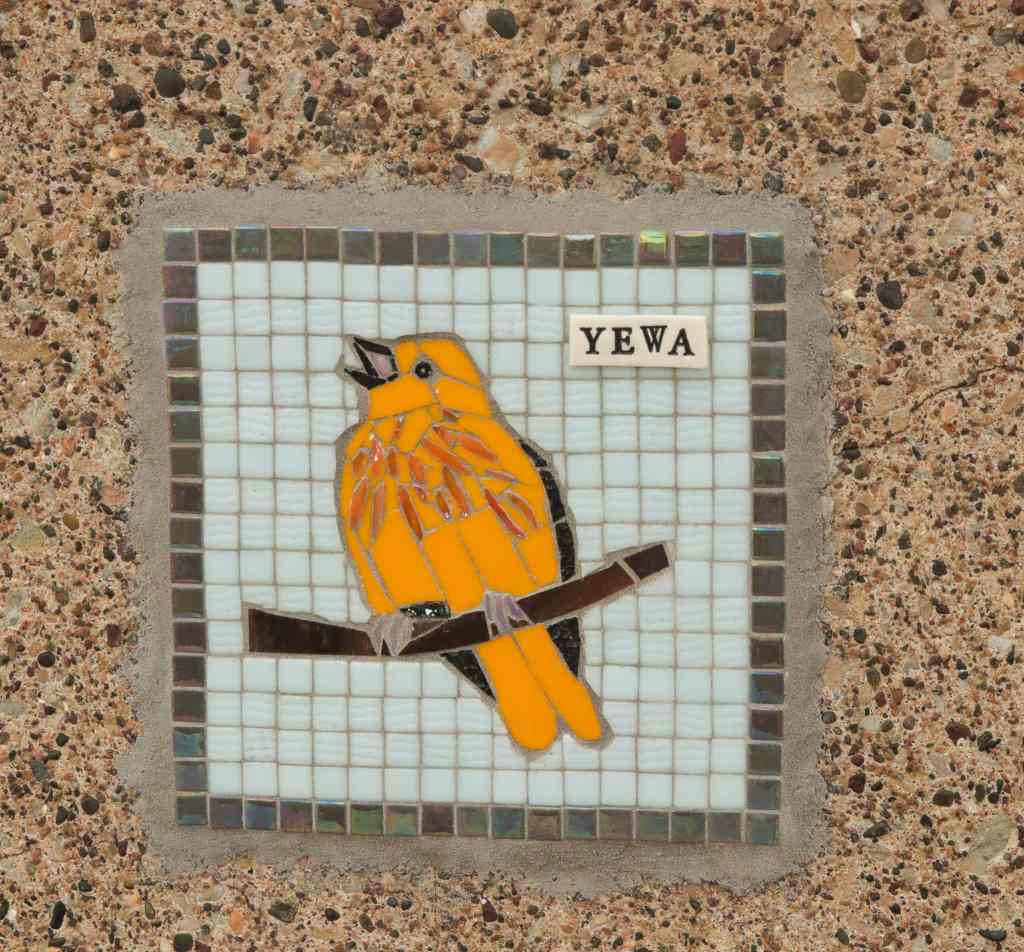

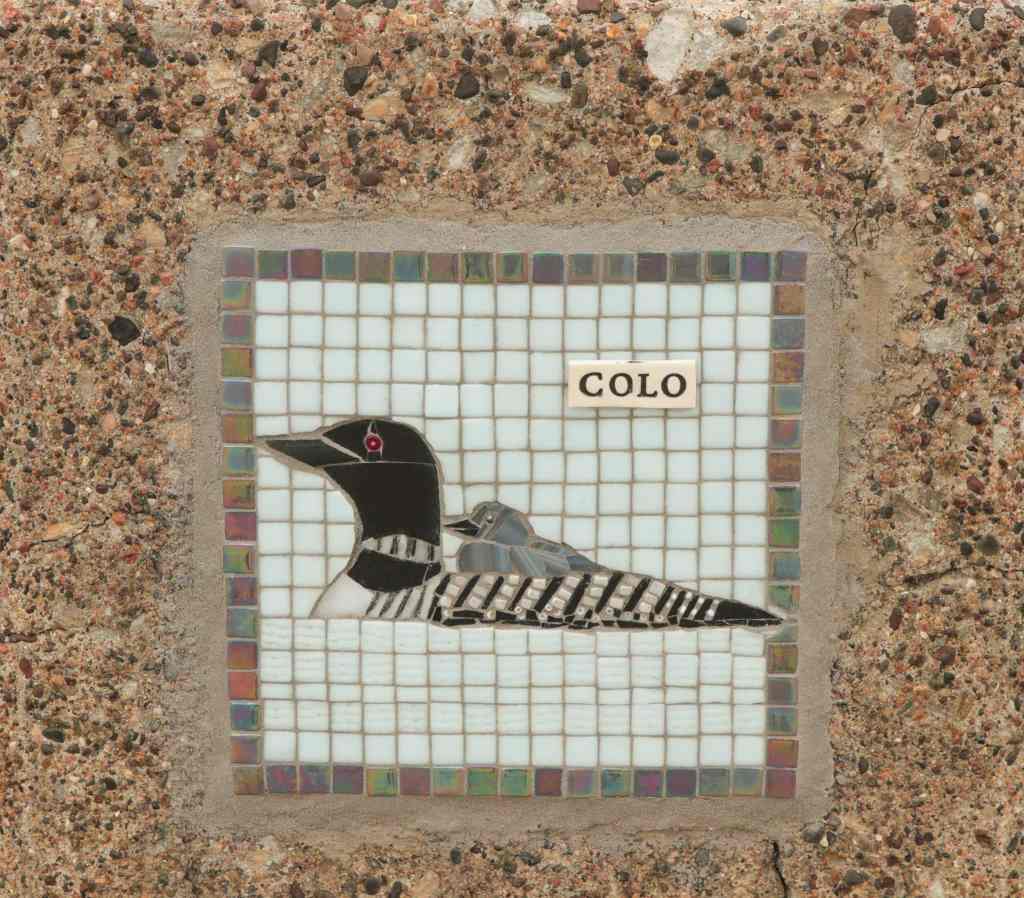

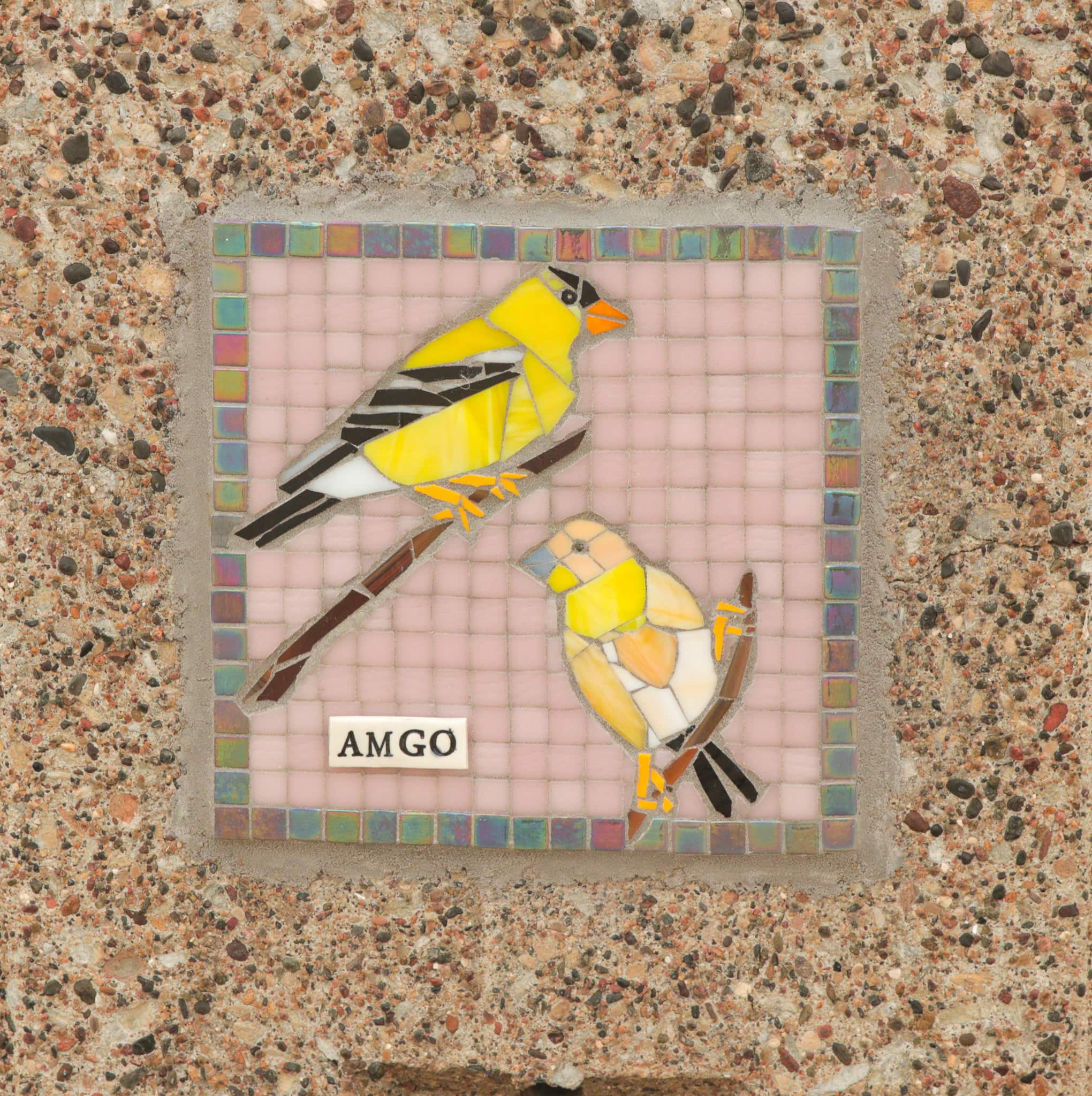

Another improvement to Lower Landing Park is the installation of 18 imaginative tile mosaics, a refreshing way to give visitors a look at some of the birds that live around the Mississippi in St. Paul. Minneapolis artist Kellie G. Hoyt created the bird mosaics.

The Industrial Zone and Pigs Eye Lake Road

Continuing east, I exited Warner Road at Childs Road, meaning the end of the safety of the protected bike path. I expended little rubber on Childs Road, turning onto the aptly named Pigs Eye Lake Road in less than a quarter mile. A quirk worth noting here is that “Pig’s Eye Park” has an apostrophe but Pigs Eye Road does not, according to the official map of St. Paul.

The barrage of signs at the intersection offered an omen of the multiple obstacles about to come my way. This is the entrance to an extremely active, highly industrial area, so it was me versus many large, heavy, fast-moving vehicles and other road hazards.

Moving south past Shop Road and the CP Rail facilities, one encounters a gravel road to Pigs Eye Wood Recycling and Environmental Wood Supply: a dusty, raucous enterprise that grinds waste trees and clean pallets into wood chips used to fuel the heating and cooling plant for Downtown St. Paul buildings.

Several hundred feet further is a second entrance to the wood facility that doubles as the road to Pig’s Eye Regional Park. The unnamed “road” is marked with a lackluster, homemade-looking sign. But hey, at least it’s now marked, unlike when I first came here.

While closing in on the park, another fifth of a mile and a hindrance or two remained. The biggest is the pothole and gravel-laden dirt swath that inadequately serves as the road. It’s also the dumping ground for debris from Saint Paul Regional Water Services construction projects, and lies along the north side of the path.

Pig’s Eye Regional Park

At last, Pig’s Eye Park! The landmark bridge just ahead spans Battle Creek.

I dismounted from my bike just as Mary deLaittre and Laura Bray, the Great River Conservancy’s other employee, parked and exited the car. The Conservancy leads advocacy and private fundraising for three large capital projects along the 17 miles of the Mississippi River within St. Paul. One is the East Side River District, of which Pig’s Eye Regional Park is a part.

“How do you bring one of the three great rivers of the world and the local community together? How do you bring the river from the edge back to the center of public life?”

Mary deLaittre, executive director Great River Passage Conservancy

I was most interested in the East Side River District, specifically Pig’s Eye Park, because of its relative anonymity, unconventional location and metamorphosis from Native land (the Dakota village of Kaposia) to a dump to a Superfund site, and finally, to an undeveloped park.

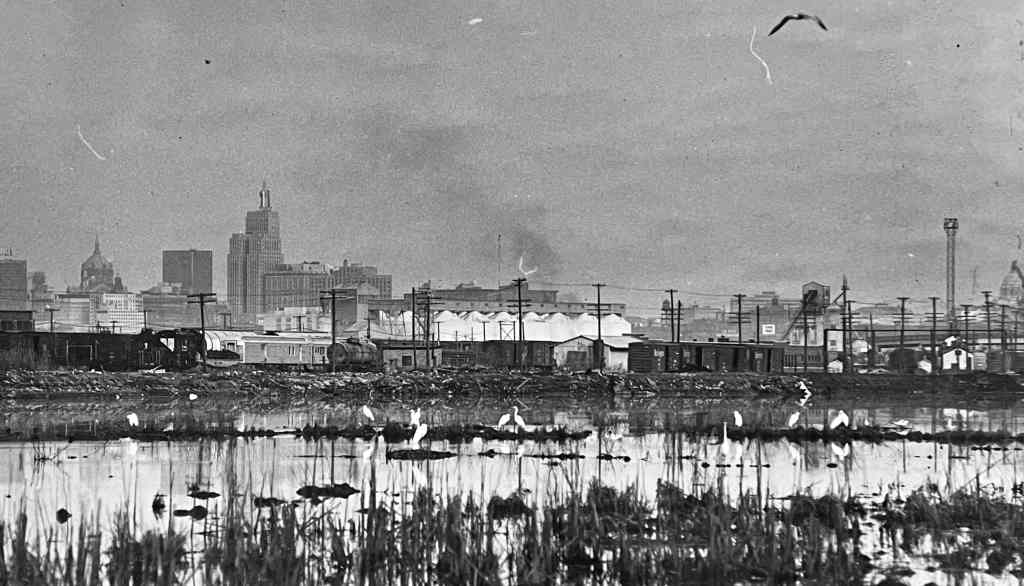

Pig’s Eye is an important and very complicated site and story, explained Mary. “You’ve got two barge terminals, water treatment facility, wood chipping facility, one of the largest rail switching yards in the region, a regional park, DNR headquarters, two Superfund sites. And then depending on who you talk to 40 to 60 percent of all migrating birds coming up from the river, come through here.” And that’s a small part of the convoluted history of this spot.

A major dilemma affecting wholesale development of the 1,200-acre Pig’s Eye Park is pollution — a large part of the park is a Superfund site. From at least 1956 (possibly decades earlier) to 1972, about 230 acres were used as a legal but unpermitted dump.

Several major corporations, a couple dozen governmental entities (including the cities of St. Paul and Minneapolis) and area residents tossed refuse and hazardous and construction waste here. Mercury, PCBs, PFAS, cyanide, lead and cadmium are some of the worst pollutants that were dumped and buried in the landfill.

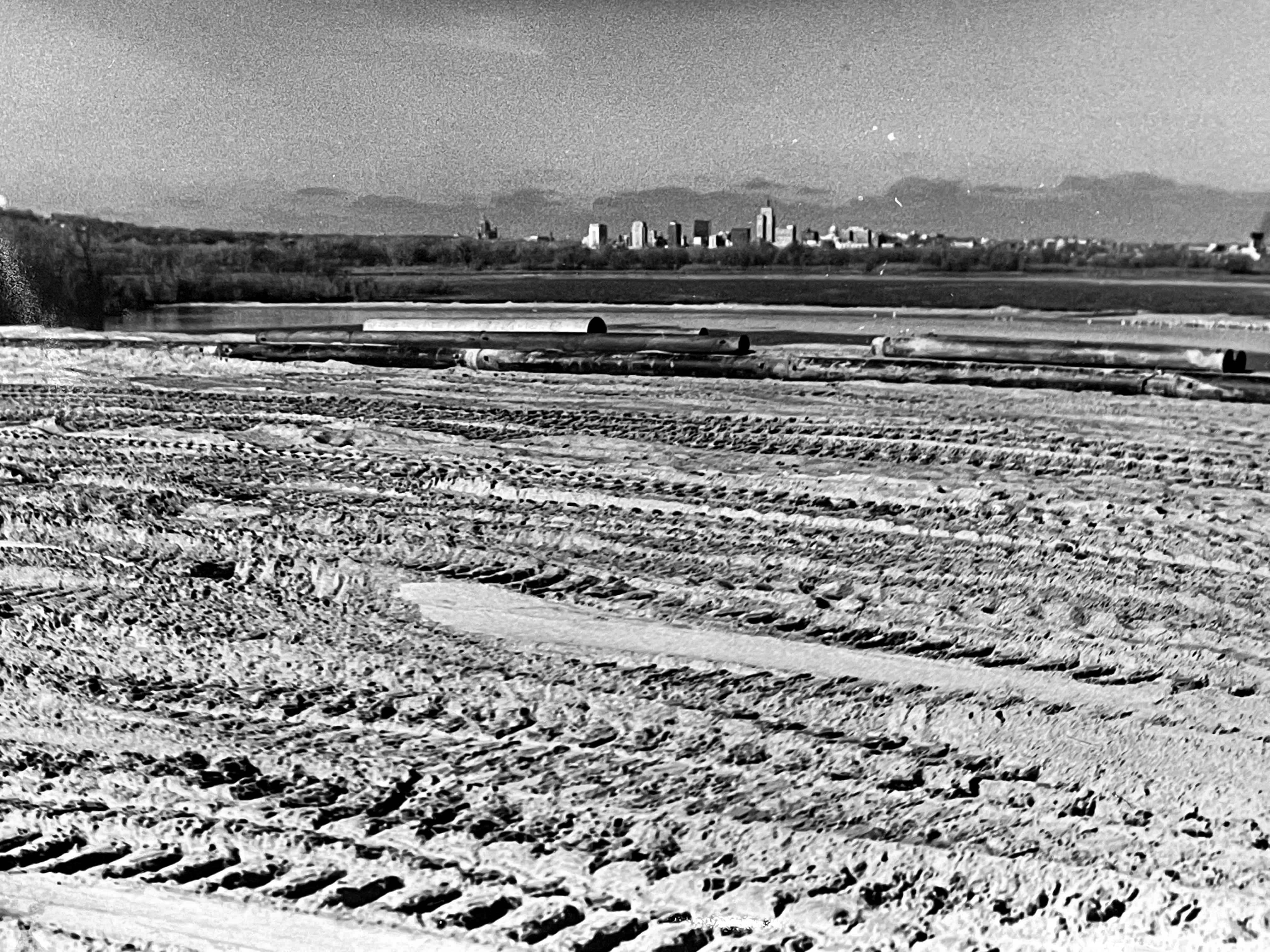

The environmental abuse continued from 1977 to 1985. The Metropolitan Council Environmental Services (MCES), operators of the nearby Pig’s Eye wastewater treatment plant, dumped ash from sewage sludge on about 31 acres of the land. Two to three feet of soil was placed over the dump but contaminants continue to leach into soil and groundwater, and construction waste and other garbage still work their way to the surface.

“It (Pig’s Eye Regional Park) is open to the public, but people are sort of discouraged from coming here because it’s very unsafe getting here. It’s very difficult. It’s an active industrial area.”

Mary deLaittre

All told, an estimated 8 million cubic yards of materials were buried, which created what remains the largest unpermitted dump in Minnesota.

Monitoring of the landfill began in 1992 and very limited cleanup started in 1999. At the direction of the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA), crews removed several hundred 55-gallon drums of toxic chemicals from 1999 through 2003. Other abatement efforts in the early 2000s included stabilizing contaminated soil, waste removal and covering 80 acres of polluted land with two feet of clean soil. Nevertheless, estimates are that millions, even billions of dollars more will need to be spent to completely clean up the pollution, if it is even possible.

The good news is that lawmakers in 2022 allocated funds for a task force that will determine how to clean up the landfill. The MPCA job posting for the Task Force Coordinator closed on November 14, 2022.

As to the best way to return the former landfill to its natural state, Mary told me, “We don’t know what shape or form cleanup will ever take.” One idea she mentioned is building a permeable wall that “would be like six layers deep of different materials. So when the water from flooding goes up and then the water from the [Battle] Creek and flooding goes down, it’s moving through this massive filter.

“You can’t pierce the clay and go down, so every anything you build has to float almost like when you’re building on permafrost,” added Mary.

Another critical part of the story of this land is that Pig’s Eye Park — Čhokáŋ Taŋka (the “big middle”) in the language of the Dakota — as well as thousands of acres beyond in all directions was Dakota homeland. With that in mind, Mary contacted the Minnesota Indian Affairs Council (MIAC) in 2016, after taking the job at the Conservancy. According to its website, the MIAC “protects the sovereignty of the 11 Minnesota tribes and ensures the well being of all American Indian citizens” in the state.

“It was very clear,” Mary stated, “that we had to work with the Dakota and local Indigenous communities to make sure their voice was heard, to integrate their ideas into the design processes, and also figure out ways, both from an economic perspective and a programmatic perspective to have them included.”

Mary added, “We’re really trying to turn the process of engagement and voice and ownership on its head and hopefully understand what the communities want to see happening here. Or, they may not want to see anything happening here. And then what does that mean in terms of community access to this location?”

The Conservancy held meetings — called “convenings” — with Native and non-Native groups and organizations. The goal of the convenings, said Mary was “so everybody could introduce themselves to one another and figure out who to work with. That is where we understood where all these gaps were around engagement.” Mary added the Conservancy has hired Full Circle Indigenous Planning + Design to increase Native community involvement in discussions “to preserve and honor indigenous culture and heritage” in the East Side River District project, including Pig’s Eye Regional Park.

Partnerships extend beyond Native groups. Convenings hosted by Great River Conservancy and the City of St. Paul included more than 20 organizations that are involved in river-related projects.

Of course, a part of Mary’s job is to give tours of the park. The most frequent reaction from visitors is surprise, she told me. “Most people that we bring down here, and we bring down people from all walks of life, never knew that this actually existed and they’re surprised at how beautiful it is.” She continued, “They’re also surprised that they’re literally surrounded on two sides by the east side of St. Paul and that the airport’s right there and that a lot of the infrastructure that supports them on a day-to-day basis or provides to the economy of St. Paul is just right here.”

After countless visits to Pig’s Eye Park, I wondered about her favorite spot. She replied that it’s the hillock just south of the bridge. “I love the prospect because you could see 360 degrees and really get an understanding of this place.”

There is no schedule for developing Pig’s Eye Park, Mary said. “We have $2.5 million of grant proposals out there right now for this project, $350, $400,000 for schematic design and then another almost $2 million for moving beyond schematic design into a project. But we’re totally funding dependent.” In other words, when the money is raised they’ll be able to move on the project. If you’d like to help fund Pig’s Eye Regional Park, the Great River Passage Conservancy will gladly accept a tax-deductible donation.

Upon completing our interview, Mary and Laura left and I began exploring the prairie portion of Pig’s Eye Park. What was merely background noise during our conversation became the unmistakable notes of the nearby industry. Rail cars banging as they coupled, diesel locomotives revving engines and blaring horns, the shrill blast of an air whistle from an adjacent factory and semi trucks passing by along Highway 61.

Still, the natural world of Pig’s Eye Park managed to break through and then push aside the industrial cacophony. The variety of bird calls was astounding — eagles, blue jays, chickadees, red wing blackbirds and more bantered. Bees, cicadas, crickets and katydids represented the insect contingent.

Below, a few of the sights I spotted on my hour-plus-long stroll through Pig’s Eye Park. (Click on any image to enlarge the gallery.)

With my jaunt through the beautiful and compelling Pig’s Eye Park complete, I continued the ride south on Pigs Eye Road to see where it would take me. Almost immediately the park transitions from meadow to forest, the stark difference because it wasn’t used as a dump.

Beyond the Park

To the west sits what is officially called the Metropolitan Wastewater Treatment Plant. It’s also known as the Pig’s Eye sewage treatment plant and occasionally, just Pig’s Eye.

Turns out the public section of Pigs Eye Road ends just under a half-mile south of the dirt road to Pig’s Eye Park.

The locked gate didn’t stop my ride, it just altered its direction. Now westbound, I entered the grounds of the wastewater treatment plant.

The Metropolitan Council is the regional policy-making body, planning agency, and provider of certain essential services in the seven-county Twin Cities metro area. The wastewater treatment plant is one of those services, as is the Metro Transit bus system, which probably explains why these buses — either newly delivered or decommissioned — are parked here.

Based upon the reaction — really, lack of reaction — from wastewater treatment plant security (or anyone else), the unnamed streets around the plant on which I road must be public.

The Return Trip

Be aware that getting to Pig’s Eye Regional Park is challenging via vehicle and dangerous on a bike. Furthermore, it has no amenities — no running water, bathrooms, benches, official trails, or trash cans. Still, Pig’s Eye Regional Park is an unpolished gem. Yes, it’s absolutely worth a visit. A stroll around the meadow is relaxing, even peaceful, if you let the sounds of nature overcome the industrial racket. The woods to the south offer the same peace in a distinctly different atmosphere. Pig’s Eye Park is also the rare spot in St. Paul where solitude is almost guaranteed.

This article first appeared in Wolfie Brownder’s blog, Saint Paul By Bike — Every Block of Every Street.