Editor’s note: This is the first installment in a series of proposals for how a local rail network could work for Minnesota and beyond.

Transit enthusiasts are used to seeing a new high-speed rail (HSR) proposal for the United States every few months — colorful and ambitious diagrams that turn complex transportation challenges into sleek graphic design. Some are meticulously researched, some are created algorithmically, others are wildly optimistic.

They all share a common trait that keeps new versions coming: They spark imagination about what could be.

And they succeed! Anecdotally, high-speed rail dominates the topic of transportation planning for the layperson. Any time the topic of urban infrastructure comes up, the topic of HSR is sure to follow. But the way it’s talked about in popular culture has a few problems.

The fundamental flaw in this focus is the disconnect from actual transportation needs: high-speed rail fails to address the daily transit challenges most Americans face. While intercity connections are valuable, the most pressing transit crisis in the United States is the lack of robust local transportation networks in all but a few places, such as New York and Chicago. In most towns and cities, residents struggle with inadequate public transit, forcing car dependency that leads to congestion, environmental damage, a less delightful urban form and significant personal expense.

A fraction of the money proposed for national HSR networks could transform local transit systems, making daily commutes and trips more efficient, affordable and sustainable for millions of people. These local networks would provide immediate and tangible benefits to far more people than a handful, or really any number, of HSR lines would. What good is a high-speed train if the best way to get around at your destination is still a car? Such an alternative to air travel strays further from being transformational and closer to being just an aesthetic difference.

Indeed, the prevalence of high-speed rail fantasies is, ironically, a symptom of the very car dependency it purports to challenge. These grand intercity rail proposals serve as a kind of transportation wish fulfillment — a way for car-dependent Americans to imagine a new kind of mobility without interrogating their daily transportation reality. The maps become a form of escapism, a safety valve for transportation frustration, a way to acknowledge transit’s potential without actually dismantling the car-centric systems that define American urban life. Most Americans can romanticize European train travel precisely because it feels distant and exceptional — a travel experience, not a fundamental reimagining of daily movement. The mental leap from admiring a French train to demanding a comprehensive local transit system remains, for many, an insurmountable cognitive distance.

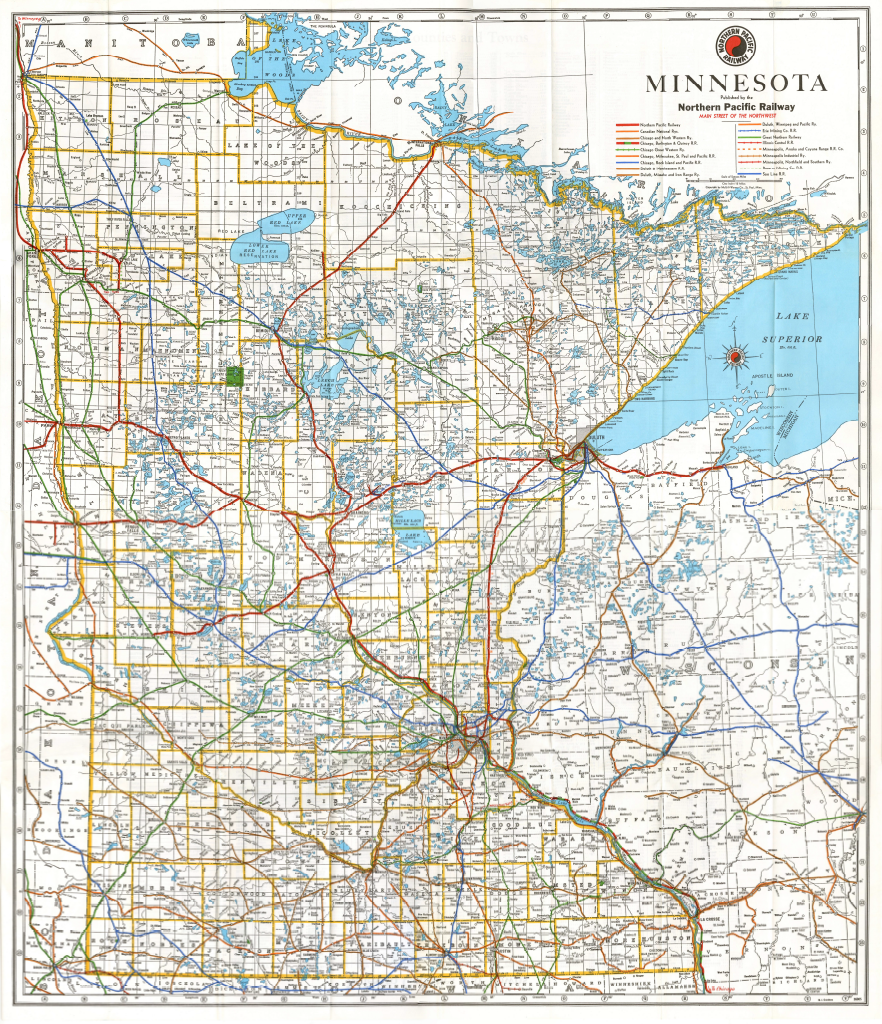

So what’s the alternative? This series will examine local transit possibilities in cities across Minnesota. To accompany this, I’ve created a regional map of my own — primarily meant to serve as a sort of “table of contents” for exploring how individual metro areas could develop their own robust transit networks. This will be the framework for the local proposals in this series of articles. Focused on Minnesota’s largest cities — the Twin Cities, Duluth, Rochester and St. Cloud — this series will ground transit in historical precedent.

By understanding how these local systems could connect, we can begin to imagine a future with better transportation. Each installment will reveal how even modest rail routes can serve local transportation in a way that also knits together the larger regional network.

Methodology

Given that this is the first installment in the series, let’s discuss my methodology for creating this first map. Drawing any transit map requires making choices, whether due to geography, population or political realities. This proposed network is intentionally simplified, acknowledging that a more comprehensive alignment would include additional stops. Historical routes through Rochester, for instance, traditionally included stations in Faribault and Owatonna — details I’ve omitted for project focus.

Alignment

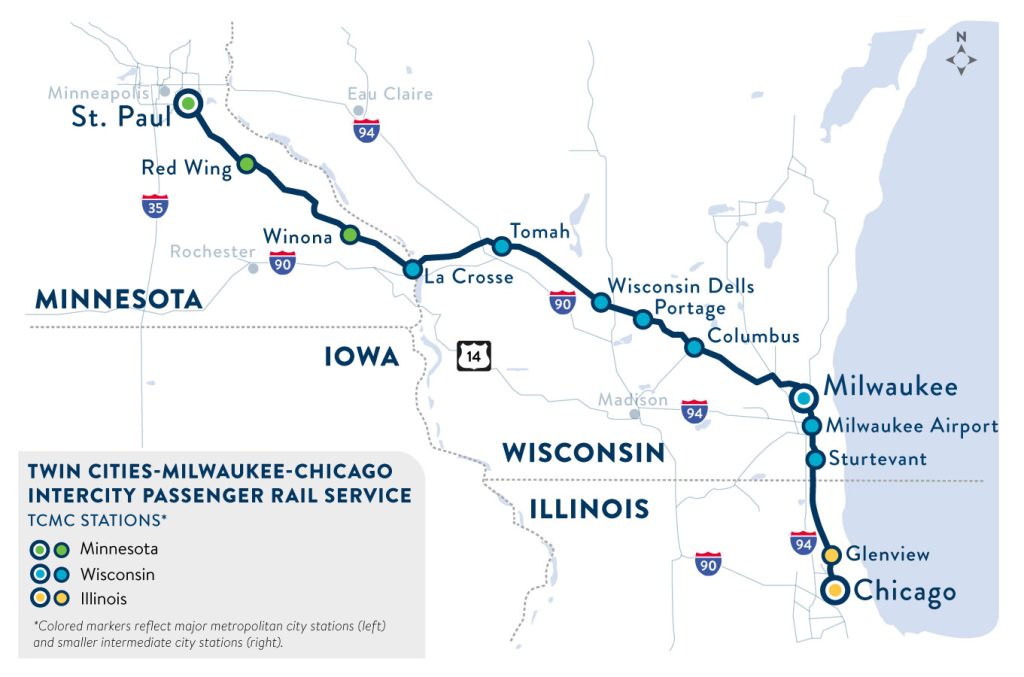

Given the importance of cost-saving when it comes to building public transportation in the United States, one might expect the train route south of the Twin Cities to more closely follow the existing passenger rail right of way (ROW) passing through the Wisconsin Dells. However, by skipping Rochester and Madison, the current passenger rail alignment is a criminally missed opportunity. The population of just those two cities is 20 times greater than the combined population of all the towns currently served by the Empire Builder and Borealis in Wisconsin (not including the cities included in both alignments, such as La Crosse and Milwaukee). Population centers like these cannot be ignored just for the sake of frugality if the goal is a network that’s useful.

Although the northern stretch of my so-called “Hiawatha Flyer” route is sparsely populated, it’s also flat and benefits from existing rail ROW. If Swiss trains can traverse mountains and valleys to serve populations measured with three digits, then surely something like a Fargo to Winnipeg route is possible here. Consider that a hundred years ago, virtually all communities in Minnesota were connected via passenger rail, from Ely to Bemidji to Marshall to Thief River Falls, and it’s on this historical basis that we lay the foundation for the map.

It also draws inspiration from modern success stories, like in Virginia, where state-funded rail connects smaller cities that you wouldn’t normally expect to be prioritized. In fact, this is a big reason why border metros — Fargo-Moorhead and Duluth-Superior, as well as Grand Forks and La Crosse — are so well represented on this map. The support from multiple legislative bodies and multiple budgets can be a powerful boon (and a politically necessary one) for rail construction.

Frequency

Frequencies are based on current flight frequencies between terminal cities. For example, there are currently two daily flights between the MSP airport and Winnipeg, and one to two daily flights between the MSP airport and Duluth. I’ve doubled these numbers for the northern part of the Hiawatha Flyer and the North Shore Express as they don’t just travel from end to end: Instead, they serve metros along the way and contain several advantages over air travel. This frequency ensures that at least one of the departures could fit into most passengers’ schedule.

Meanwhile, there are 12 to 16 daily flights between MSP and Chicago, which presents a slightly different calculation. I deliberately scaled back the frequency here, recognizing that although the demand is high, at 12 trains per day it would already be operating at higher frequencies than almost anywhere in the country. Going even higher feels unrealistic, especially given that the Borealis and Empire Builder would likely still exist in these scenarios.

Speed

The estimated end-to-end times provided in the proposal are not minute-accurate, but they are based on precedent. In the 1930s, trains traveled from the Twin Cities to Chicago in five and a half hours. Accounting for nearly a century of technological advancement, a five-hour journey seems not just feasible, but conservative. Not only is this speed competitive with a flight to Chicago, but it can be done without the airport security process, without needing to transfer to another train to reach downtown from the airport and all while in a vehicle that’s more spacious, quiet and better for the environment. Not to mention that it easily beats the six hours it would take to drive to Chicago from the Twin Cities, as well as the eight hours it takes via the Empire Builder or Borealis today. While the latest in train technology could halve that proposed time further, even a century-old speed is still competitive with modern infrastructure.

In conclusion: While this series begins by sketching out regional connections, the path to better transportation doesn’t start with expensive high-speed routes between cities — it begins with addressing how people move within them. Each successive installment will dive into a Minnesota city along these routes, examining how local transit networks could transform daily life while fitting into this broader web.

With this regional map to help organize our thinking, we’ll start the real work of building better transportation at the local level — one city, one network at a time.

Author’s note: I welcome your comments, suggestions and ideas on the Streets.mn Bluesky or Facebook accounts.