As with all downtown freeway projects from the 1960s, the construction of I-94 through Minneapolis demolished a huge portion of the community and tore the remains in two. The Hennepin-Lyndale “Spaghetti Bowl” interchange is an egregious example of excessive space devoted to motor traffic at the expense of local residents, and it continues to be a barrier between neighborhoods to this day.

As we near the end of I-94’s life-cycle in downtown Minneapolis, it’s time to think about the future of the freeway in the heart of our city.

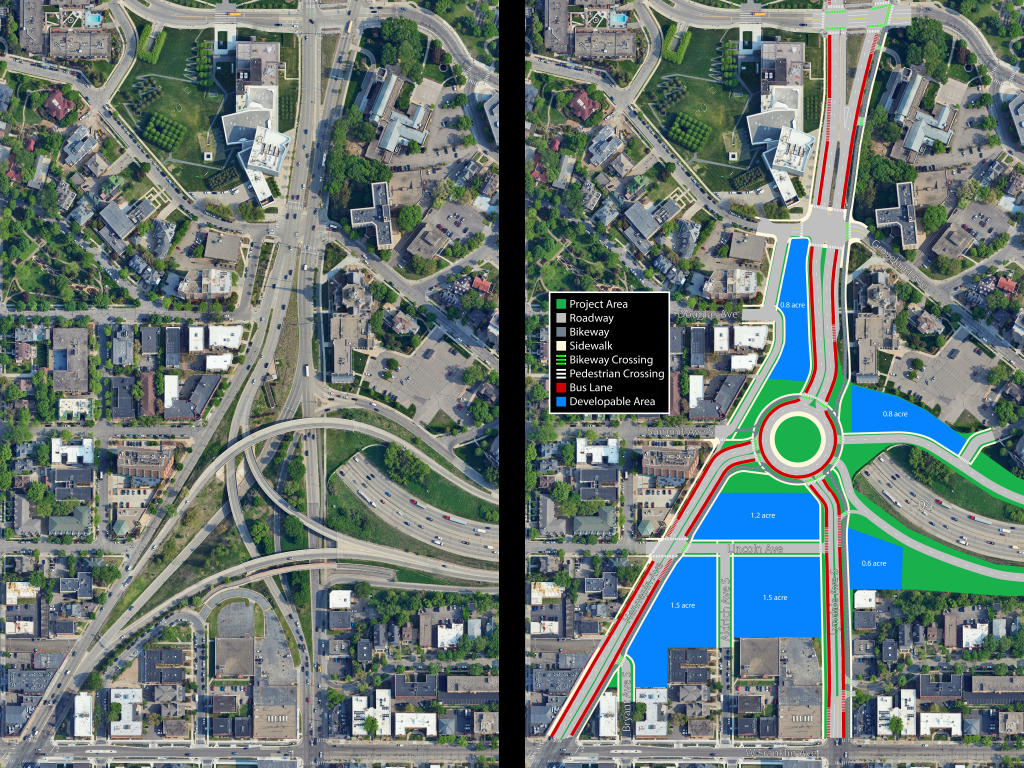

Comparisons from before I-94’s construction reveal its enormous scale. Entire city blocks were bulldozed to make room for flyover ramps so vehicles could blast through at high speeds without regard for pedestrians. Now more than 50 years later the layout remains unchanged, leaving the Loring Park and Lowry Hill neighborhoods permanently divided. A first-person look at the area shows just how vast and hostile the space is when crossing on foot, leading most people to avoid the area altogether.

The Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) is currently examining St. Paul with its Rethinking I-94 project, but the portion through downtown Minneapolis and to the west was removed from the study shortly after it began. While reconstruction of the Hennepin-Lyndale bottleneck may not be feasible in the short term, I’d like to offer a vision of what a better future in Minneapolis transportation could be — the “turbo roundabout.”

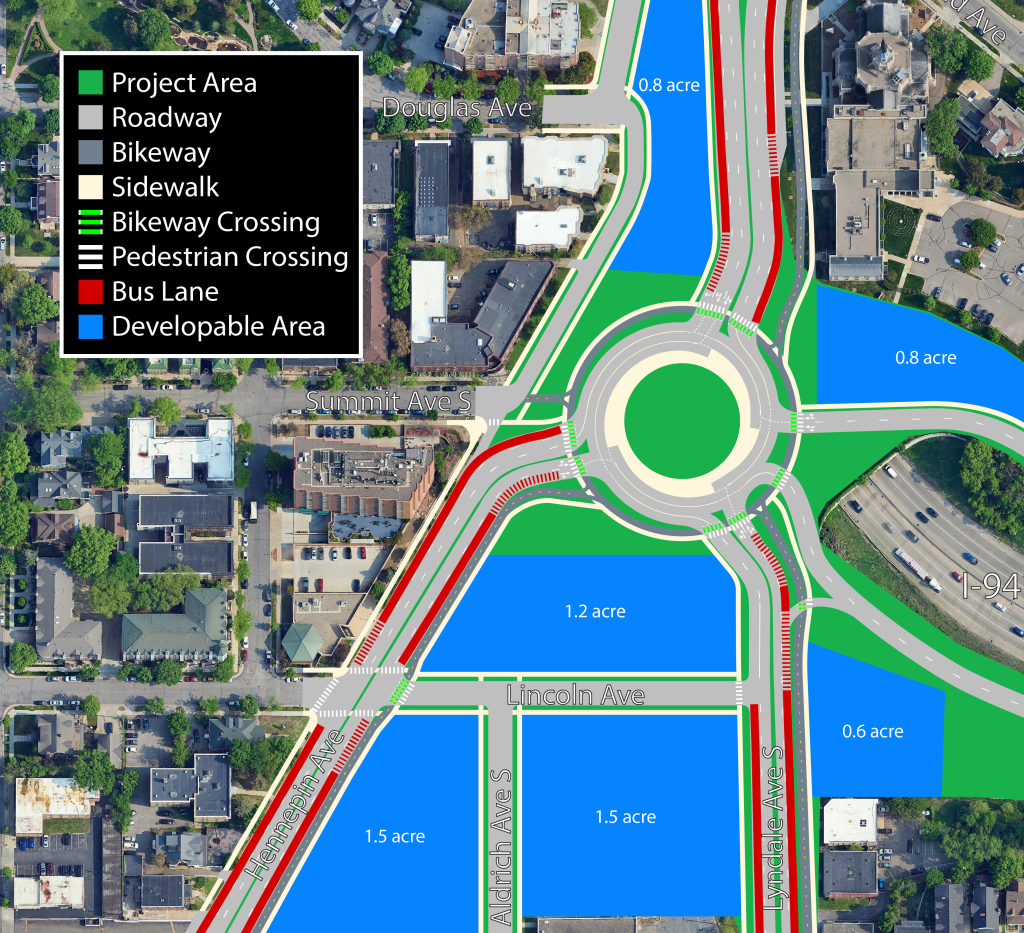

Looking at the current interchange, I was struck by how much space the highway ramps took up. As an amateur mapmaker, I sought to create a solution that returns this incredibly valuable land in the heart of the city to productive use. With the proposed roundabout, more than six acres of developable land is recovered along with a restored street grid. The space can be used for housing, businesses, parks, or whatever else the community desires. Bus lanes and bikeways are both compatible with the Hennepin and Lyndale reconstructions currently underway to the south. Cyclists can also seamlessly ride north from Hennepin, Bryant, or Lyndale to the Loring Greenway without needing to climb up an awkward overpass.

One of the primary benefits of a roundabout is safety. Roundabouts are known to be much safer for all road users due to slower speeds, fewer conflict points, and the elimination of T-bone or head-on collisions. Studies in Minnesota show an 86% reduction in fatal crashes and an 83% reduction in serious injury crashes where roundabouts have been installed. A Dutch study finds similar safety benefits for a high-tech “turbo roundabout.” The benefits are clear for those outside of a motor vehicle — slow speeds makes the environment safer and more welcoming to all pedestrians and cyclists.

Contrary to how the name sounds, a turbo roundabout is not about increasing speeds. The design is meant to reduce conflict points and keep vehicles moving slowly but efficiently for a high throughput. Vehicles choose a direction before entering the circle, then stay in the same lane throughout their journey as the roundabout spirals them to the correct destination. Although the design is Dutch in origin and most common in the Netherlands, turbo roundabouts have recently begun finding their way to the U.S.

Beyond safety, removal of the multi-layer highway interchange will also make huge strides toward reconnecting Loring Park and Lowry Hill. Reducing the overall size of the interchange allows developments on either side to be physically closer together, meaning they take less time to walk between. Pedestrian crossings are shorter and more accessible, enhancing this effect of closeness. In addition, removing overpasses and embankments means that one can clearly see across the street, making the whole area feel like a single neighborhood rather than two separate worlds. A bird’s-eye rendering makes clear just how much land is recovered by efficient use of space and how much closer the two sides can be.

Simplifying the interchange down to a roundabout also provides great cost-savings in the long term. Highway infrastructure is notoriously very expensive — complex engineering behind flyover ramps and traffic signals leaves millions of dollars in maintenance costs even for a simple interchange like at Lowry Hill. By contrast, a roundabout isn’t much more involved than a basic city street, mainly requiring resurfacing every few decades.

As it happens there is only one other roundabout currently within the bounds of Minneapolis, the Godfrey Circle in Minnehaha Park. That leaves an opportunity for the Lowry Circle to become an iconic landmark, the “gateway to downtown Minneapolis,” as others have put it. While Minneapolis has made a concerted effort to install traffic circles on local streets, taking the next step to rotor-ize our major thoroughfares would put the city on the path to a safer, more sustainable future.

All these benefits will not hinder smooth traffic flow for motor vehicles. By eliminating traffic signals, a roundabout allows continuous flow of vehicles without stopping, giving a more pleasant driving experience.

Then there’s the elephant in the room — vehicle capacity. About 63,000 vehicles travel through the bottleneck daily, according to traffic counts taken in 2023. Minneapolis estimates a peak hour to be 10.5% of daily counts, giving a maximum flow of about 6,600 vehicles per hour. Using the turbo roundabout design gives an estimated capacity of 4,500 vehicles per hour. At first glance it looks to be coming up short, but we must first take into account the phenomenon known as traffic evaporation. Much like induced demand, where an increase in road capacity will result in an increase in vehicle traffic, reducing road capacity has been shown to reduce demand for car travel without harming overall mobility.

The above traffic counts were gathered in 2023. In 2024 Minneapolis began construction of Hennepin Avenue to the south, reducing from two car lanes in each direction to one. Hennepin County is currently reviewing designs of Lyndale Avenue to the south to be constructed in 2027. Again, each design reduces from two lanes to one. North of the intersection, Minneapolis added bus lanes in 2024 which reduced general traffic from three lanes to two. Taking a more conservative estimate that traffic reduces by 33% in the coming years (in alignment with the northern lane reduction), that brings our 6,600 vehicles in a peak hour down to just under 4,400, well within the roundabout’s capacity. With the exciting changes from both Minneapolis and Hennepin County in recent years, this could be the first opportunity where a simple, safe roundabout can serve the needs of the bottleneck without compromising capacity.

Looking Ahead

With how poor the current design is, there has been no shortage of other proposals on how to improve the junction. Some focus on maximizing recovered land by realigning the street grid. Others use a roundabout to make the space safer and more pleasant to cross. Streets.mn contributor John Van Heel’s Rethinking I-94 West plan gives a more comprehensive vision for the entire I-94 corridor through Minneapolis, including Hennepin and Lyndale. And while the city of Minneapolis did make some improvements during a 2014 reconstruction, the overall structure remained the same. I add my version to the pile to encourage everyone to be imaginative in what our constructed environment could be to give future Minnesotans the best quality of life possible.

What would be the path to completion for this plan? Hennepin Avenue is under the jurisdiction of Minneapolis, Lyndale Avenue is controlled by Hennepin County, and the interface with I-94 may require state-level involvement as well. Design and construction would be a huge cooperative effort between these entities, though not something that hasn’t happened before given the updates made in 2014 and 2024. In the hopes that this doesn’t become another plan that sits on the shelf, I will be discussing with officials at Minneapolis, Hennepin County, MnDOT, and other relevant organizations to uncover the feasibility of this plan and understand how visions like this become reality. Stay tuned for an updated story on what could happen next at Hennepin and Lyndale.