You can probably think of a street corner in your neighborhood that’s a little too dark to feel safe walking at night, or a place where SUVs speed past you instead of letting you cross at a crosswalk with your dog. Maybe a local park needs a little love or a bike rack.

If you’re unusually connected, you might know that St. Paul offers a chance every two years for its citizens to apply for funding for these types of neighborhood improvements by submitting a grant-like community-sourced proposal.

The problem is, most residents of St. Paul haven’t even heard of the Capital Improvement Budget, aka CIB, and aren’t likely to be bothered to figure out the complicated criteria and system for submitting such a proposal. In short, there’s room for improvement. A lot of room.

St. Paul City Audit in Progress

The City of Saint Paul’s Audit Committee is currently undertaking a study of the CIB process. In December 2024, they finalized the scope of an audit of the CIB process, to be completed by Wilder Research. The main focus of the audit is to address three categories of questions: Process, Community Engagement and Equity.

Staff from Wilder, in collaboration with the city’s Office of Financial Services, have been interviewing city staff, CIB Committee members, City Council members and community applicants. A final report is expected in March 2025.

Both of us were invited to be interviewed as part of the audit and have shared feedback with the city. And now we want to share it directly with you, in the hope that more St. Paul residents — and a greater diversity of residents — will take notice of and participate in the CIB process in the future. Our suggestions for improvement will come in Part 2 of this article; in Part 1 we will address: What is the CIB, anyway?!

What is St. Paul’s ‘CIB’?

The focus of this article is the community-based “Community Proposals,” part of the larger Capital Improvement Budget (CIB) process. This community process takes place every other year in even-numbered years. Particularly high-scoring community proposals (more on scoring later) can then be recommended for city funding outside the conventional department-based and -led funding and planning mechanisms. (The more overarching CIB itself is actually a much larger and more conventional funding process, which is beyond the scope of this article; for the record, we also aren’t aware of an equivalent community-proposals program in Minneapolis.)

Below is an example of a funded and completed CIB project. Rectangular Rapid Flashing Beacons (RRFBs) were installed to improve safety for the pedestrian crossing at the intersection of Selby Avenue and Ayd Mill Road — you can see them between the pedestrian crossing signs and the arrows in this image from Google Street View.

Each of us has submitted multiple proposals — some chosen for funding, but most not — in 2020, 2022 and 2024. Our proposed projects included bike and pedestrian safety infrastructure, sidewalks, street lighting, bike racks and park improvements in our neighborhoods (most within the boundaries of Union Park District Council, where we both serve on the board, but some elsewhere or citywide).

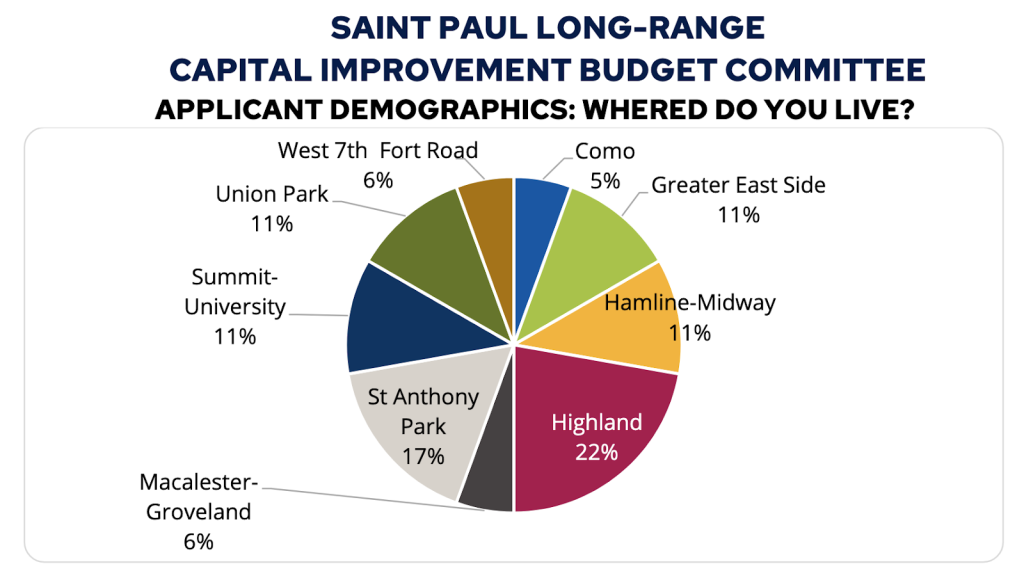

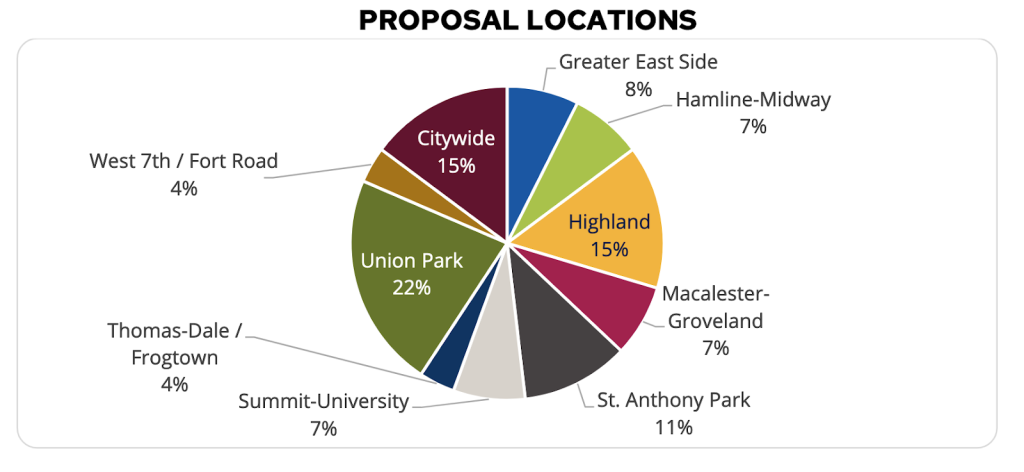

Unfortunately, as it stands today, the community-facing CIB process has too many ideas from too narrow a demographic (read: white homeowners like us), and too little addressable budget to pursue the vast majority of even low-hanging-fruit proposals. Once we scrutinized the process itself, it became clear why only certain people with time and expertise can successfully submit a proposal with some chance of success.

Current CIB Proposal Process

Before we get to the problems with the process, we’ll give a brief overview of the rough guidelines for CIB Community Proposals. As you’ll see, this isn’t exactly straightforward.

First, in order to be funded, submitted projects must be objectively capital in nature. This means things like buildings, streets and streetlights. Monies cannot be used for operational expenses like employees or programming. The projects must also be on property owned by the city of St. Paul, be for public use, and have a useful life of at least 10 years. These are must-haves, and without meeting this as a first step a Community Proposal won’t even be officially considered for CIB funding.

During the last three rounds of CIB applications, depending on the year, city staff has sometimes asked for a preliminary proposal, followed by a more complete grant-style application if the preliminary proposal appears to pass muster. In our experience, it is common for city staff to nudge the proposer after identifying key deficiencies, essentially giving a chance to gently amend a proposal in order to meet this initial threshold for consideration. For example, could another location be selected that is city-owned, or could the proposal be modified to last at least 10 years?

Second, projects that meet the initial threshold are evaluated and scored by members of the volunteer CIB Committee based on a numerical scoring system (see below). Applicants are invited (but not required) to give brief presentations about their proposals to the committee at a public meeting.

Third, the CIB Committee approves a final list of projects recommended for funding. The limited budget means they can’t just fund the highest-scoring projects, but have to figure out how to fund the most and/or most worthy projects possible, according to their judgement.

Finally, after a long and highly procedural CIB review process (including many meetings, which are open to the public and sometimes held at different locations around the city), the mayor receives the CIB Committee’s suggestions and then selects the projects to be included for funding in the next year’s city budget, to be approved by the City Council. Ultimately, elected officials can ignore the committee’s recommendations and scoring and make an entirely different selection, if desired!

The lengthy review of submitted Community Proposals under the CIB are subject to both objective and subjective criteria for evaluation, and feedback and hand-holding are inconsistent at best. This process clearly isn’t for the faint of heart.

By the way, the city has only $1 million to use each cycle. That makes this process highly competitive, and we can say from experience that a lot of worthy projects go unfunded.

Summary of Criteria to Evaluate CIB Proposals

Objective Criteria

- Must involve building something: infrastructure, not operational expenses like employees or programming.

- Must be on city property (watch out for streets like Snelling Avenue, University Avenue, Shepard Road, or Maryland Avenue that are actually owned by the county or state).

- Must be for public use.

- Must have a useful life of at least 10 years.

Subjective Criteria

Proposals are scored numerically (0-6) in the following categories.

- Condition: A “very good” project “addresses a critical and urgent need (health/safety risk), significantly extends life of asset or fills a gap in the system.”

- Usage: Current and/or potential use of the project.

- Equity and Inclusion: A very good project “clearly describes a need for the proposed project that is specific to the community that, if unmet, will contribute to disparities. Clearly advances equity, inclusion and accessibility.”

- Strategic Investment: Defined by the city as “collaboration, innovation, or alignment with City/neighborhood goals and plans.”

- Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED): This is generally the idea that crime can be prevented by creating and maintaining public spaces that allow people to feel safe, move freely and see freely. The specific criteria are:

- Natural surveillance

- Natural access

- Territorial reinforcement

- Physical maintenance and activity support

Complicated Process, Inconsistent Results

In 2022 the scores for the various criteria, along with the averages used for the final ranking, were made public; the numerical scores for individual projects were not released with the final recommendations in 2024.

Similar projects submitted in different years appear to have been scored very differently. A “bike racks in parks” project was ranked fourth out of 43 projects in 2022 and recommended for funding. Basically the same proposal (the only big difference was bike racks in different parks) was ranked in the bottom 50% of the projects in 2024.

The map below shows the bike racks proposed in 2022 that were recommended for funding (blue) along with the racks proposed in 2024 (orange) that were not. Locations were proposed based on city information about parks lacking bike racks.

A proposal to improve pedestrian safety at Skyline Tower and Midway Peace Park (at Griggs Street and St. Anthony Avenue, near the Midway Target) was not funded and ranked in the bottom 50% of project proposals in 2022. The same proposal, with no substantial changes, was ranked highest on the list of projects recommended for funding in 2024.

Problems with Implementation

In theory, each even-numbered year the CIB Committee would review community proposals in the spring and provide a list of projects proposed for funding by the end of June for inclusion in the mayor’s proposed budget in August. In practice, these deadlines have not been met. In 2020, the CIB process was disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic and failed to follow the timeline. In 2022, the CIB approved its final recommendations in mid-July.

In 2024, the CIB Community Proposal process was closed and then later extended to solicit and encourage more applications in order to have at least one project proposal per city ward (the initial round lacked any proposals from Wards 5 or 7). The process was initially announced March 7 and closed March 24 after receiving 20 applications. The process was reopened May 13 with a new deadline of June 15.

Ultimately 27 projects were reviewed and ranked in the committee’s initial recommendation on August 12, 2024, with the final recommendation including six projects as of the committee’s meeting last October 14. Two projects (a pedestrian crossing at Skyline Tower and traffic calming on Jefferson Avenue) originated from the first round of applications; the other four came from the second round. Projects were recommended in all wards except Ward 3, with two in Ward 7 and one in Ward 5. Projects recommended for funding included pedestrian and traffic safety projects, resurfacing a basketball court and neighborhood lighting improvements.

In the final adopted Capital Improvement Budget, published to the city’s website in February 2025, the six recommended projects plus an additional project — improvements to Indian Mounds Regional Park in Ward 7 — were funded, with additional monies coming from remaining funds from previous years’ CIB projects.

Going unfunded doesn’t mean projects are unworthy; given an unlimited budget, any and all of the projects proposed would be useful improvements for St. Paul residents.

Stay Tuned for Part 2

Check back in a week or so for Part 2, in which we offer suggestions for how the CIB process could be improved. Visit the Streets.mn pages at Bluesky and Facebook to comment on this article.