In 2016, after the first election of Donald Trump, Streets.mn cofounder and longtime contributor Bill Lindeke wrote a “Map Monday” short piece, commenting on the apparent stark urban/rural divide on the Minnesota electoral map. In it, he asked what “social, personal and political strategies” might be employed to overcome the divide. Now, eight years later, Lindeke has commented as well in his weekly column on MinnPost about the lamentable fact that urbanists lost continuity of support when former President Donald Trump won yet another election. He is referring to the big infrastructure items, like rail, that cities can’t really do alone. Certainly, rail and bike lanes and sidewalks are a boon to any city, but can things like this be disentangled from whatever mess is causing progressive urbanism to fail?

One month prior to the 2024 election, I wrote an article looking at in-country migration trends in the U.S. where I posited that something within progressive policy — either social, personal or political — is failing in progressive and urbanist locales; most notably in the places which bear the standard of those policies: the large “blue” metros like Chicago, Los Angeles, New York City and even the Twin Cities. After the election, it seemed to me that I might have touched on some fundamental truth of the electoral reality for progressive policy.

There are two points to address regarding Lindeke’s articles, vis-à-vis my own, in connection with the 2024 election results:

- Eight years later, it appears that the divide is closing, not because it has been bridged, but because voters are merely coalescing around, or migrating in response to, what they reject.

- Should people want continuity of progressive and urbanist policies if those policies are failing?

On the Supposed Divide

In the 2024 election, as predicted, former President Donald Trump won an increased share of votes in rural counties. Surprisingly, the same is true in urban counties. Had urban counties voted for Vice President Kamala Harris in margins equal and opposite to rural counties, it would have been clear evidence of a stark, widening divide; but instead, urban areas shifted in the same direction as their rural counterparts. Voters in rural Minnesota counties increased their support for now President-elect Trump by an average of 1.77% this cycle while the counties won by Harris increased their vote share for Trump by 0.52%. (I painstakingly clicked through the entire Minnesota State Department interactive map for this; really would have been nice to have a condensed spreadsheet.) These numbers are not population weighted, but are simple arithmetic and geometric averages.

Because these are geometric means, very sparsely populated Lake and Cook counties in the arrowhead, which saw a decrease in support for Trump by -0.15% and -0.41%, respectively, carry equal weight in my 0.52% average with Hennepin and Ramsey counties, which both increased their Trump support by +0.14% and +0.94%, respectively. Remove Lake and Cook counties and the other five counties won by Harris — including Olmstead which shifted towards Harris — exhibited a +0.7% shift toward Trump. Still, however, these statistics are geometric means and are not population weighted.

To consider this shift in terms of population: within Hennepin and Ramsey counties alone, the increase in the number of voters who cast their vote for Trump is equal to 64% of the entire population of Cook County, or approximately 3,608 voters. While rural counties all added Trump votes, none alone added 3,608.

Not only did Trump get 3,608 more votes in the metro in 2024 than in 2020, a whole lot of people in the Twin Cities just did not show up: comparison of estimated votes cast and voter registration roles show 97,825 and 44,700 registered voters who did not cast a ballot in Hennepin and Ramsey counties, respectively. This absence could indicate dissatisfaction with Democratic-controlled government, or identity-based fracturing of the Democratic base or even passive support for Trump. These calculations of percentage swings are simple arithmetic and are not weighted for voter turnout or for overall vote share out of total eligible voters, however, are still representative of broad voting trends within Minnesota.

Hennepin and Ramsey counties saw 5% lower voter turnout than in 2020: 53,760 fewer people voted. The cause of this turnout reduction is open to interpretation, but the number absent voters is 3.3 times the entire population of the two rural counties that shifted away from Trump. If the current electoral map looks as, if not more, starkly divided than in 2016, it is because the pre-existing Democratic margins in the remaining blue pockets were padded to crash-rated levels.

Sahan Journal, which took the time to do better math than I did, showed a shift in Ramsey County of 2.24% more Republican. That is a considerable alignment with rural counties.

In 2016, Lindeke cited the New York Times’ take on the growing urban/rural divide, which might have not only been false, but also a red-herring distracting from the actual electoral divisions and what they meant for the future — that is, now. According to Politico, in the 2024 election, former President Trump made nearly 10-point gains in Queens and the Bronx; this electoral change is indicative of a seismic swing toward alignment of those urban areas with rural counties. Vice President Harris might have still won the Five Boroughs, but Democrats should not necessarily feel good about that. Such a large swing in an era where political opinions are said to be polarized and ossified constitutes an electoral train-wreck. Ms. Harris only won because those areas had pre-existing, immense, front-impact resistant Democratic margins.

“Seismic” is a term I also used in my previous article to describe the rate at which young families have been fleeing blue/progressive/urban centers for years now. (In fact, regarding the declines in New York City, I described it as akin to a demographic asteroid impact.) Furthermore, I had forecast that in the long term, the accelerating demographic trends boded ill for progressive and urbanist policy, contrary to the faith that many liberals have held that eventually demographics alone would render the Republican party electorally impotent. My gravest error in that statement was the timeline in which smug political laziness would come around to claim progressives. It’s not the long term: It’s now.

Politics and Demographics

The demographic trends continue unabated. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, California is poised to lose four seats in the Electoral College in 2030. The so-called “Blue Wall” states are also poised to lose Electoral College seats. If the 2030 Electoral College projections were applied to the 2024 election, there are scenarios in which Vice President Harris holds on to part of the “Blue Wall” and still loses the election.

If demographics are, indeed, destiny, then at this point the projections are pointing strongly toward a destiny of continued Republican dominance of government. If the status quo continues, the only way for Democrats to overcome their shortcomings will hinge on the idiocracy, which former President Trump seems intent on installing, creating such ruin that there is a veritable revolution at the ballot box. However, if your party’s only hope is the ruination of millions of Americans, then your party does not have a viable platform.

All of which brings us to the political, social and personal failings, to be addressed in that order.

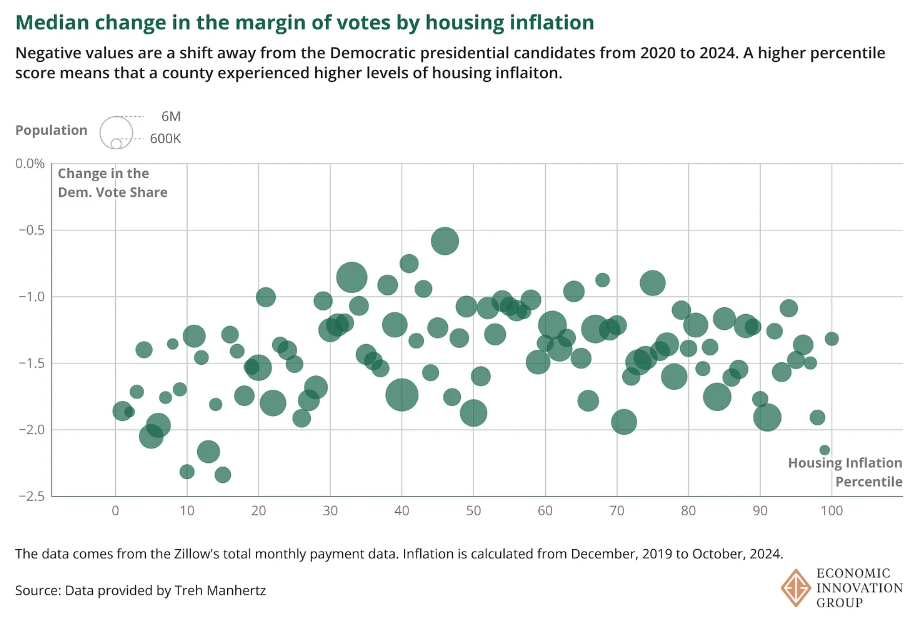

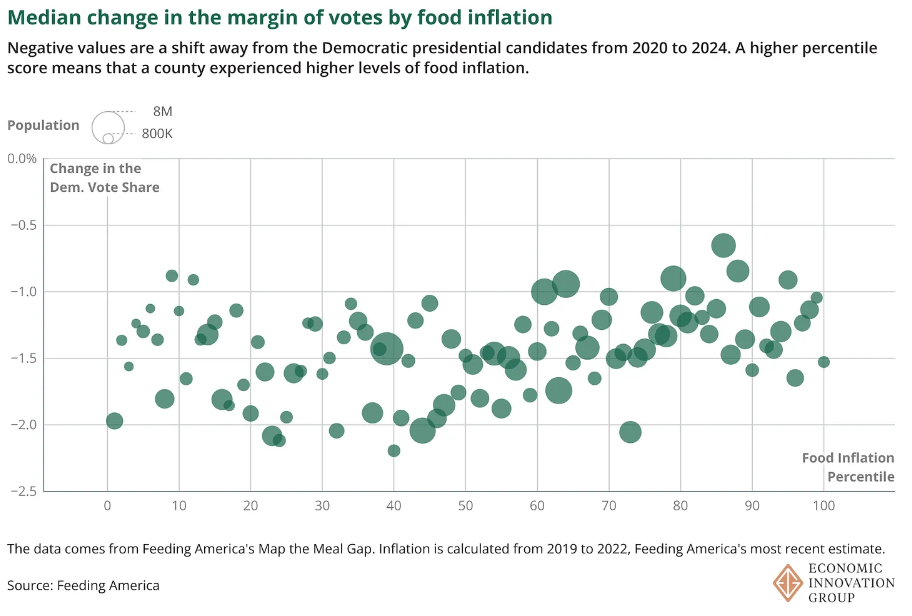

Just as the most proximate cause of the progressive and urban exodus is housing costs, the most proximate cause for the national election results is inflation. To quote Democratic strategist James Carville, “It’s the economy, stupid!” But, as more maps from the Economic Innovation Group (EIG) show, decline in Democratic support did not correlate evenly with inflation rates across the country. While inflation was arguably the primary drag on voter turnout in general, and certainly impacted support for Democrats, the effect was not magnified by higher inflation numbers. The rightward shift appears uniform everywhere whether inflation was 5% or 10%. There is no trend line showing that the higher the rate of inflation, the greater the gains for Republicans, or the loss for Democrats. If inflation was the simple cause factor, one would expect that there would be a strong relationship between actual inflation rates and voter behavior.

However, one relationship does stand out strongly: support declined sharply in the most expensive and most populous places, mirroring the general dissatisfaction outlined by several years of in-country migration trends. The large urban metros that Vice President Harris won showed, in fact, the sharpest losses of all compared with President Joe Biden in 2020. Those places have had progressive/urbanist governments for a long time, and it’s not going well for anyone. Even if it is as simple as inflation or housing, the governments of those places have not found a way to mitigate their communities’ problems.

At a national level, it’s not entirely fair that Vice President Harris should be made to shoulder the blame for the failings of government in California, Illinois or New York, while former President Trump does not have to answer for different but significant failings in Louisiana and Alabama, but that’s politics. However, demographic data suggests that California and New York may be emblematic of the greater failings of progressive/urbanist policy and also shows that voters do not want national continuity of support for those policies.

Local Democratic governments — progressive and urbanist governments — have had a very long time to address the ills of their communities, longer than the Biden administration has been in place. In many places, they have been entrenched for decades. If they were succeeding, then the policies they have implemented and the ideas for which they serve as amplifiers would be spreading. People, instead, are fleeing. Voters around the country are voting against the specter of government or culture they have not experienced, while the voters that remain within those cities are shifting sharply away from the powers that be.

This realignment is a simple political failing of progressive and urbanist Democrats who have enjoyed power for a very long time. While I wish, this time, voters had prioritized high-minded notions like the rule of law, and not-returning-threats-to-democracy to the White House, voters also recognize actual policy failures.

To put it bluntly, before California Gov. Gavin Newsom or Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker start posturing about 2028 presidential bids, they should probably show that they can govern a place where people want to live. Voters are not stupid.

Social and Cultural Shortcomings

Regarding social (cultural) issues: On election night, I believe it was David Brooks on PBS who commented that we might be seeing, in part, the fallout of years of white liberals treating Latino, Asian and even Black voters like identity groups, rather than like voters. He’s absolutely right; even before “peak-woke” around 2020-2021, highly educated white liberals were more likely to perceive racism toward minorities than minorities were, more likely to call for “defunding the police” than minorities wereand more likely to saddle minorities with white liberal ideas that they don’t want, like the absurd term “Latinx.” Needless to say, white liberals have not experienced the racism they are so up in arms about, nor likely have they ever had a negative interaction with the police. They probably don’t speak Spanish, either.

Typically, the lines of political polarization, particularly in progressive circles on social media, are portrayed as follows: On one side are older and whiter people who are resentful about a changing world and who live out in the suburbs and in those big, empty red counties on the electoral map; on the other side are vibrant, young and very diverse “woke” people (mostly brown, probably female or non-binary, but good white “allies” do their part.) This group lives in the metros that voted for Hillary Clinton and Vice President Kamala Harris — the metros that Secretary Clinton described as “the places that are optimistic, diverse, dynamic, moving forward.” Also, the places, I would add, that are starting to hollow out. This binary geographic and “identity” division is false.

The fact that progressive activists were badly losing the social “culture war” was previewed in 2018 in a voluminous study titled “Hidden Tribes: A Study of America’s Polarized Landscape.” (Worth a read!) The authors of the study divide Americans instead into seven “tribes”: Progressive Activists, Traditional Liberals, Passive Liberals, Politically Disengaged, Moderates, Traditional Conservatives and Devoted Conservatives. The latter two groups, in 2018, comprised roughly 25% of the population, and their views fell rather far outside the mainstream.

What cut across nearly every tribal line in this study, however, was a distaste for “political correctness,” a term that only a year later would be more commonly called “wokeness.” The “woke” are in a clear minority across all ages and all racial demographics. In fact, the only group that indicated strong support for political correctness was the smallest “tribe:” Progressive Activists. Progressive Activists are the most homogenous of all the “tribes.” They are nearly entirely white, and twice as likely as any other group to make more than $100,000 per year. Even the Conservative “tribes” are more racially and socioeconomically diverse. Furthermore, Progressive Activists have dominated government, policy and social discourse in the “blue” urban centers for decades now. Progressive Activists are not only the smallest and most homogenous “tribe,” but their views fall further outside the mainstream than that of the two Conservative “tribes.” If there is a divide, that’s where it is.

In 2024, former President Trump saw some of his largest gains in New York City (and across the country) among Latino voters, despite more than a decade of Progressive genuflecting before the altar of identity. It might still be about the economy, but progressive and urbanist governments have tokenized and fetishized those brown voters with all the evangelical virtue-signaling they could muster, and delivered nothing of value. The woke/progressive fixation with race and identity can often feel as alienating in its own way as many of Mr. Trump’s own statements about Latinos, Asians and more. The class and education “grievance politics” of the Trump campaign might be lamentable and even ugly, but woke identity politics are also grievance politics, no matter how many soft PR terms or how much positive affirmation language they are dressed up in. People, I think, feel that class and education grievances have a solution somewhere, but identity grievances are stratifying and forever.

In the final tally, it appears that 19 million Biden voters from 2020 stayed home. The bulk of them were not members of a broad Democratic/Progressive/what-have-you base. In 2020 they were voting against Trump, not for Biden. Now they’re not voting for anything.

The Personal Take

Since Lindeke asked in 2016 about the personal experience, and since we’re right back where he started, I’m going to relay a few personal anecdotes from my time living here, which started, incidentally, in 2016. The political and social bleeds into the personal, particularly if you live, as I do, in a place heavily populated by Progressive Activists.

It’s in small municipal issues, like when my neighbors and I attempted to have a discussion with the City Council about the assessments levied for a project on our street that the city badly mismanaged, and what we got in reply was a smug lecture on what assessments are. To go along with that mismanagement are the nearly punitive property tax rates that don’t seem to go very far. It’s the fact that we pay so much more per student in our schools than they do in the Kansas schools my niece and nephews attend, but we seem to get so much less for it. It’s the fact that my eldest child’s school wouldn’t even reply to my attempts to engage them about their broken processes, but did metaphorical backflips trying to contact me to support my magical brownness when they found out that I’m a minority. (I’m Japanese, Cherokee, English-Scottish and German Jew.) It’s the offensive “anti-imperialist” (read: anti U.S.) history “sources” in the school claiming, as one example, that the Japanese liberated the Philippines from the boot of U.S. oppression. (Yes, that claim should make you throw up in your mouth.) It’s the prioritization of identity over educational efficacy or standards of conduct and behavior. To be fair, this isn’t a public school, but a “public charter” run by — you guessed it — white Progressive Activists.

It’s the language policing, the ever-evolving and increasingly opaque linguistic constructions of Progressive Activist culture. It’s the many people who are desperate to be offended. In fact, the culture in urban centers dominated by Progressive Activists feels like living in a city-sized HR department. It’s highly unpleasant, where social interactions are warily parsed using a Progressive patois seemingly derived from a blending of HR jargon and highly dubious therapy language. And it’s the numerous purity tests that accompany Progressive Newspeak, which as I suggested I think candidate Harris ran afoul of in the election, and which I have certainly run afoul of myself.

A few years ago, a well-meaning, local Nice White Liberal acquaintance reached out to me to ask if it was OK to send her kid to school with a bento box for lunch, or if that was cultural appropriation. After my initial outburst of laughter, I realized she was earnestly serious. I then replied that “I’m part Japanese…cultural appropriation is my culture” and proceeded to talk her off the virtue-signaling ledge. It might be ideologically comfortable for a great many Progressive Activists to live in a culture of walking-on-eggshells, but most people are tired of it. All of this is petty stuff, but it all permeates the zeitgeist, and the zeitgeist alone can potentially make a big difference to a low-engagement voter living in our current miasma of misinformation. It certainly contributes to cultural divides.

I moved here because as a kind of moderate liberal guy, I wanted to live in a place that had the trappings of “urbanism,” like good bikeability and walkability. I wanted to live in a place with high education levels, and that tended to be “blue.” Perhaps that makes me part of the problem of the Great Sorting. Incidentally, if the premise of the Great Sorting is true, then the demographic trends of the past four-plus years are even more damning for Progressives.

I, personally, could have lived anywhere, and I chose this “blue” island because it seemed the ideal nexus of values and livability. Since moving here, factoring in the social and personal environment, I’ve often found Progressive Activists to be somewhat unlikable. (And, to be fair, I feel like they often don’t like me, either.) On the other hand, I really like a lot of people back in Kansas, and Texas, and Oklahoma who have voted for and support things that appall me. I’m a fairly high-information and engaged voter, so who I like didn’t sway my vote, but insofar as feelings are a component of electoral outcomes, maybe a lot of the “politically disengaged” people around the country are voting, in part, based on the kinds of people they like. (I still hope that only a small minority actually like Mr. Trump himself.) Personally, I don’t know what to do about any of that.

The Takeaway

There are a lot of opinions on what the reason is that former President Trump won so decisively. It’s not one reason though, just like it’s not one reason people are fleeing Democratic urban centers. And there’s nothing to suggest a deepening urban/rural divide lies at the heart of the election outcomes, despite the appearance of the map. The brutal summation may be that the small group of Progressive Activists who have largely defined the Democratic party for over a decade are unlikable people governing increasingly unlivable places, proselytizing an unpleasant culture, and over all of it was the long shadow of unhappiness about the economy. Taken all together, the whole could be so much more than the sum of the parts. The stunning result is that a merely slightly larger group that is also radically out of touch with the mainstream has engineered what could be a sweeping, enduring, multi-ethnic and multi-class voting coalition. In other words, the kind of voting coalition that Democrats have always dreamed of.

The final irony is that not only did the Harris campaign’s three-month effort to overcome more than a decade of ingrained impressions about policy and culture fail to connect with the great “exhausted majority,” but it also splintered the very small Progressive Activist core over all the issues that make them unpopular to begin with. Many of them stayed home because they disagreed with the Biden administration’s stance on the conflict in Gaza or Harris’ record as California’s Attorney General, or because they wanted her to do something about immigration other than appeal to the right, or because she vowed to have Republicans in her Cabinet and was attempting to bridge party divides by campaigning with conservative Liz Cheney.

Progressive Activists will likely take the loss as a kind of vindication and seek to assert greater Party dominance. This would be a mistake. People have been voting with their feet already for the past four to five years. The Electoral College forecasts are not fantasy. Three months in our ever-present cacophony of misinformation was never enough time to suddenly connect with that exhausted majority.

One might argue that the 2024 election results — not only Mr. Trump’s decisive win of the Electoral College and the popular vote, but the trifecta with Congress, too — indicate that the urban/rural divide is closing, however fractiously and unpleasantly given the options available. Now, if “urbanism” is to survive — at least the parts that can span political tribal boundaries like good infrastructure and walkable and bikeable communities — it will need to be unbundled from a lot of the things in which it is tribally bound up. Right now, it’s like an old-school cable plan, where in order to get ESPN and the SciFi channel, I have to buy a lot of garbage I really don’t care about. Eventually you start to wonder if it’s worth it.

Out of all of this, we still need to find ways to bring people together to build healthy communities that we all want to live in. Call it “urbanism” if you want. It will be tough without Federal support — indeed, with a federal government that wants to destroy rather than build — but people are still looking for something to vote for, and the work has to start somewhere.

Editor’s note: To respond to this or any article in Streets.mn, please visit our pages on Facebook and Bluesky.